Why the "Streaming Wars" Are Actually About Product Channel Fit

Meaning, it is not about "streaming wars", but whether streaming services understand product-channel fit to reach their target audiences at scale

In my call with Hedgeye's Andrew Freedman earlier this week, I mentioned that I no longer believe the term "Streaming Wars" applies to the OTT streaming marketplace. The reason is actually different from IAC Chairman Barry Diller's "Netflix has won this game" narrative I have used before.

I think these wars are more about marketing, as CuriosityStream's Devin Emery aptly summarized in a conversation about HBO Max's Action Park:.

There are tons of things on Netflix's homepage that never come close to being a major hit. Even more key is ubiquitous access (as close as exists), so that when that WOM fire does light, it doesn't get doused by people not being able to find or access the content.

— Devin Emery (@DevinMcCueEmery) October 5, 2020

"Ubiquitous access" summarizes why Netflix's on-platform and off-platform advantage: marketing. It is always one click away, whether via Instagram or TikTok, Snapchat or Twitter, Whatsapp or iMessage. It is now one thumb-tap away on Chromecast remotes, too.

So, to rephrase Devin's point, Netflix has ubiquity in part because of its marketing. When Netflix says 99MM households watched Extraction, what it is saying is that was able to reach 99MM households across multiple platforms to convince them to go to Netflix to watch Extraction.

So how do we think about non-Netflix hits like The Mandalorian or The Boys?

Here is how Netflix describes its process in a blog post dating back to 2018:

Imagine if you had to launch the digital marketing campaign for the next big blockbuster movie or must-watch TV show. You will need to create ads for a variety of creative concepts, A/B tests, ad formats and localizations, then QC (quality control) all of them for technical and content errors. Having taken those variations into consideration, you’ll need to traffic them to the respective platforms that those ads are going to be delivered from. Now, imagine launching multiples titles daily while still ensuring that every single one of these ads reaches the exact person that they are meant to speak to. Finally, you need to continue to manage your portfolio of ads after the campaign launches in order to ensure that they are kept up to date (for eg. music licensing rights and expirations) and continue to support phases that roll in post-launch.

These are the moving pieces of "ubiquity". Last quarter, it cost $2.25 per subscriber (193MM subscribers worldwide, and $434MM in spend) for the ubiquity model. That's super-cost effective.

Neither Disney nor Amazon Prime Video is anywhere near where Netflix is in terms of ubiquity. We know Disney spent an estimated $210 million on Facebook ads for Disney+ in the U.S., alone, in the first half of 2020. But, if U.S. users for Disney+ total 40MM (NOTE: my estimate), that means Disney spent 2x Netflix's marketing average on Facebook, alone. This implies inefficiency where Netflix continues to find efficiencies.

But, both have existing audiences at scale (Disney's Star Wars fans for The Mandalorian, 150MM Prime Video users across 200 countries and territories for The Boys) to whom they can market internally or externally. That was certainly evident in Disney's success with the WandaVision trailer, which racked up 53MM views in its first 24 hours.

There is no competition over audiences here - they already have been aggregated, at scale, easy(er) to reach, and awaiting something new from their preferred service or brand (Disney).

If It's Not "The Streaming Wars", Then What Is The Right Term?

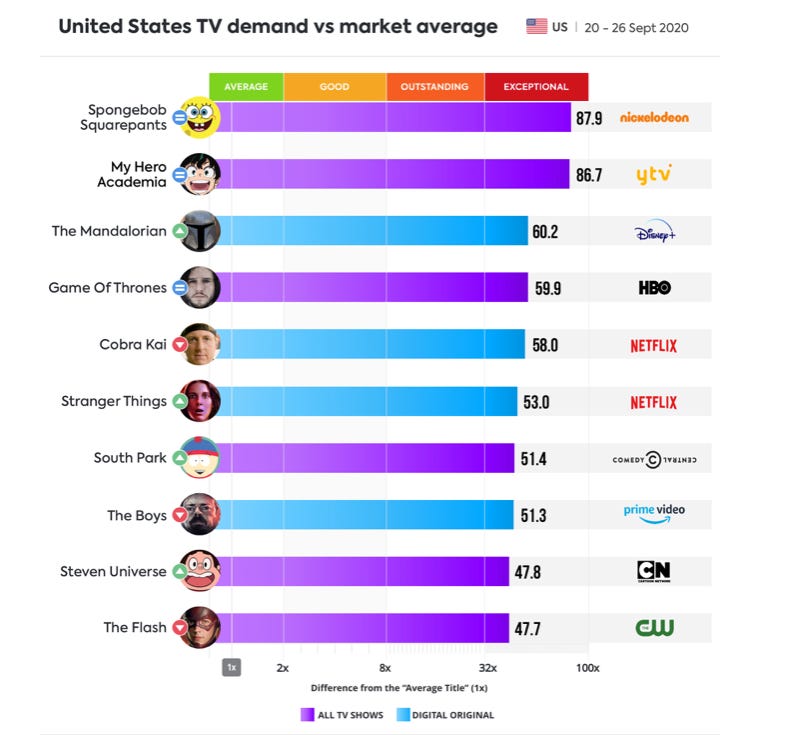

This Parrot Analytics chart - from today's The Entertainment Strategy Guy post, "The Content Battles are Competitive in the Streaming Wars" - fleshes out the power of Netflix's ubiquity,

I don't entirely buy into Parrot's "demand expressions" logic (and I think The Entertainment Strategy Guy makes a good point: "I have concerns their data overrates the conversation around super heroes and genre"). That said, I do think this highlights an important point: excluding Netflix (Cobra Kai, Stranger Things) these are all either shows with established fan bases at scale (Spongebob, The Flash, South Park, The Mandalorian), or on channels that have scale (HBO at ~36MM U.S. households) or on platforms that have scale (The Boys on Amazon Prime Video), or simply target a hard-core niche (anime shows Steven Universe or My Hero Academia).

In other words, there is no competition here between these platforms, channels, shows, and niche content. This is not a ranking of competitors. Rather, this is a list , if not an array, of shows that are succeeding unusually well within their particular distribution channels.

These are shows that have found unusual success with channel-market fit (about which I wrote two weeks ago on Roku). That has certainly been the case with Cobra Kai - it was successful on YouTube, but it did not help YouTube Premium grow, and now it has been extraordinarily successful on Netflix (see chart above).

So, the data we are getting on "the streaming wars" are not about war or zero-sum; rather, I would argue they are about which companies are savvy enough to understand the marketing required to drive scale in those channels where it finds product-channel fit. Rankings like the chart above tell us which ones are figuring that out, and how well they are succeeding with product-channel fit, nothing more.

Netflix continues to win the game because it has solved for near-ubiquitous product-channel fit. No one else is coming close to its model, or its marketing economics.

Also...

I just posted my Mic Drop #3 on my Landing & Rolling Substack. I realized about halfway through it was going to be longer than planned given the news in AVOD from the past week. Will aim for shorter next week.