Investors See More Data Transparency, Creatives See Less in Streaming

Investors are seeing more transparency with data as streaming services scale, but creatives are seeing less

With Jeff Bezos stepping down as Amazon CEO and Andy Jassy assuming the role, one question which has emerged is where Amazon Prime Video goes from here.

A key problem is, because Amazon has not been transparent with Prime video data, we know little, if anything about Amazon Prime Video. Perhaps our best window comes from this interview with an anonymous Amazon employee:

What’s an example of a division that AWS subsidizes particularly heavily?

Prime Video, for one. Jeff loves Prime Video because it gives him access to the social scene in LA and New York. He’s newly divorced and the richest man in the world. Prime Video is a loss leader for Jeff’s sex life.

There is probably truth to this - as the fiduciary vs visionary framework reflects, executive incentives matter. But, Prime Video is also an app with users across 50MM+ Fire devices. Prime Video has utility for which users are willing to invest up to $120 in a Fire device and $120 per year in Prime fees.

An obvious place to go from here would be diving into the future of Amazon Prime Video (or into what it means for Amazon Prime Video to be a loss leader, which the Entertainment Strategy Guy did a good job with this week).

The obstacle is the lack of transparency: we have little to no objective evidence from Amazon about how Andy Jassy perceives the Prime Video business, other than he likes sports and music, nor how management not named Jeff Bezos perceives the business. [NOTE: We also know very little about its efforts with IMDb TV, other than its total AVOD audience now reaches 55MM users.]

This lack of transparency is not unusual in the streaming marketplace. On Sunday night, Blumhouse Producer Jason Blum participated in a discussion on Clubhouse with A16Z co-founder Marc Andreessen, complaining about transparency in streaming, specifically how “Netflix doesn’t share any data” and “That’s part of the deal when you accept their huge upfront check”. [NOTE: these typically are not recorded, so I was not taking notes and instead rely on this Twitter thread which was accurately capturing quotes from the discussion].

After recent Q4 earnings calls, I think we are at a crossroads for transparency in the streaming marketplace, and a surprising new dynamic is evolving. Transparency, as a practice, is evolving away from the Curse of the Mogul-type opacity. Whereas before media companies shared little with investors, now they are sharing more. But creators are finding themselves receiving less data - the services are not sharing it, and third parties offer a limited lens.

That shift in transparency for both investors and creators has been playing out in fascinating ways in the streaming marketplace over the past few weeks.

Transparency in Q4 2020 Earnings

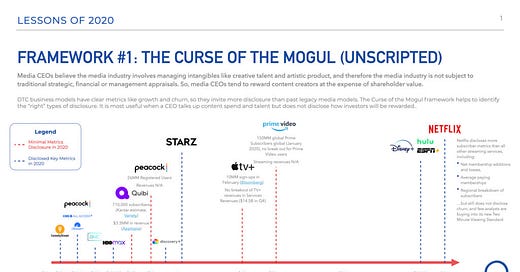

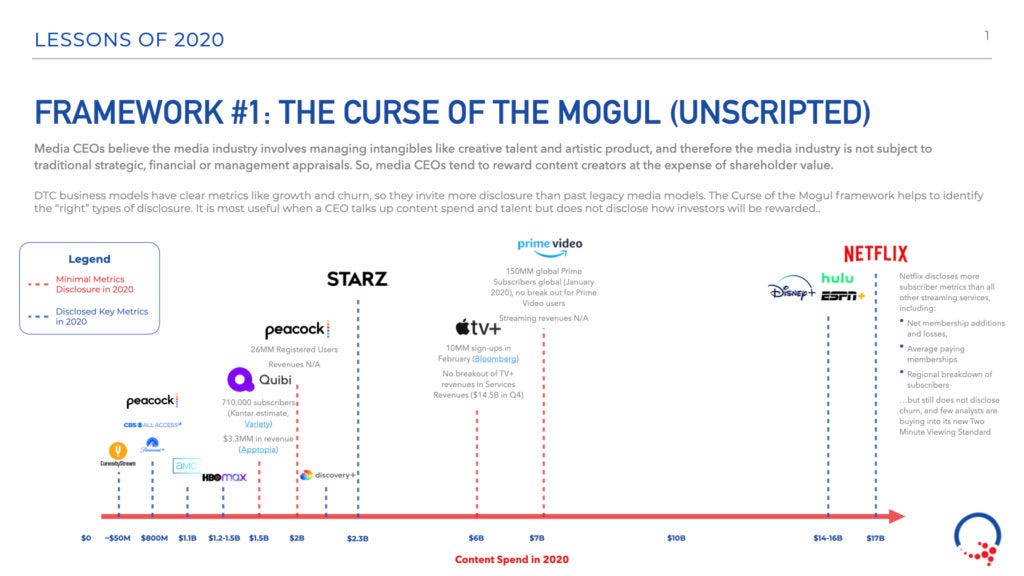

The Curse of the Mogul slide from my 2020 Lessons, 2021 Predictions is, in one way, a basic overview of transparency across the streaming marketplace. Prime Video was marked as a company which disclosed few metrics in 2020 (above).

Disclosure is inevitably going to become more common as these businesses scale and mature into core drivers of legacy media businesses. But, as we see with Amazon and Apple to date, we still may not see disclosure for streaming services that are more tactical in nature.

The transparency in Lionsgate's (Starz) and AT&T's (HBO Max) earnings are notable because they move the needle in our understanding of how their streaming businesses work by clearly defining the different buckets of OTT subscribers.

Starz is transparent, sharing how many OTT subs they have, and breaking them out domestic versus international (14.6MM total, 9.5MM domestic) We have a better story about their business partially because Roku shared a successful marketing campaign with Starz back in Q2 2020. We also know that their content focus is on women and "traditionally underserved audiences":

We've been converting and scaling Starz into a modern data-driven global subscription leader that has become the first traditional service to have more over-the-top and linear subscribers, a critical digital inflection point. By the end of next quarter, we expect streaming revenue to surpass traditional for the first time, as well.

Domestically, our programming for a broad spectrum of women and traditionally underserved audiences is differentiating us from our competitors, driving subscriber acquisition and retention, and setting new viewership records. New series P-Valley and Hightown, and the docu-series Seduced, are resonating with our audiences. Power Book II: Ghost set viewership and acquisition records in its first season, becoming the highest performing new series ever on Starz. With its initial season ending on a viewership high, we're bullish on the performance of future seasons, as well as upcoming installments of the Power franchise, Raising Canaan and Force.

That said, they are not entirely transparent. The OTT service is included with the Starz media networks segment, so we do not have data for what President Allison Hoffman means when she says:

…we've got returning franchises like Power. I think we've got three installments of power coming next year. We've got Outlander coming next year. So, in terms of driving the business, in terms of subscriber acquisition and in terms of retention, we've got sort of that nice flow of flowing viewers from one show into the next as well as sort of adding and building viewership and building the subscriber base as we go. We're always -- as per Jeff's note about in terms of the data, we're really always driving to the lowest subscriber acquisition cost. And so that's really how we manage the business. We are managing the business, to have a really good return on our marketing investment and a really strong return on our content investment as well.

Their subscription acquisition cost may be low, but unlike for a Netflix (which in in its most recent 10-K revealed reduced spending on advertising to $1.45 billion from $1.88 billion globally in 2020), we have no way of estimating marketing cost per existing subscriber or new subscriber.

Roku helps us to fill in the picture - they are relying heavily on Roku to reach target demographics for its Power series to scale cost-effectively. Roku highlighted Starz’s success on its platform last Q2:

In Q2, the most-used subscription services on the Roku platform grew quickly, with key services nearly doubling their aggregate streaming hours year-over-year. Roku was the No. 1 connected device based on hours streamed for Disney+ in the week following the release of Hamilton, according to Comscore, OTT Intelligence, July 2020. U.S. Premium Subscription services within The Roku Channel, such as Showtime and Starz, achieved significant subscription gains through extended free trial offers.

We know that Roku helped Starz to grow in exchange for ~20% of subscribers obtained. But, we have no insight into how much Starz spent on Roku or anywhere else to obtain those subscribers. On top of this, we do not know how many subscribers signed up for the discounted promotional deals Starz has been marketing on the service.

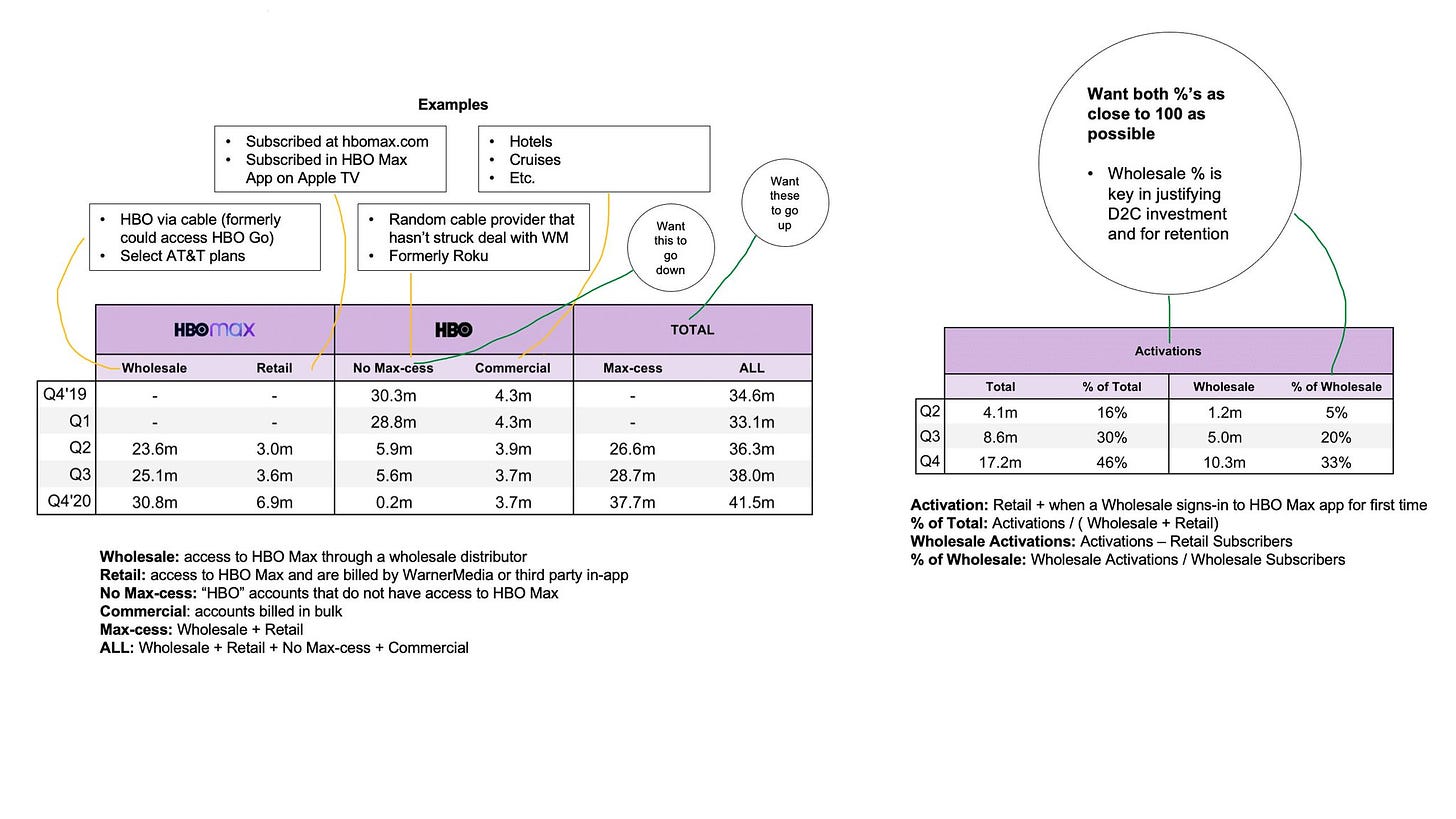

Similarly, HBO Max has become transparent, almost to a fault, about how it is defining an HBO Max subscriber. The math is messy depending on the question we ask, as I wrote in my Landing & Rolling Substack two weeks ago, and as this infographic from ANTENNA Research breaks down.

Because WarnerMedia CEO Jason Kilar has been unusually transparent in his posts on Medium about his decision-making during COVID, we are able to deduce that subscribers went up by 10.3MM in Q4 in large part because of Wonder Woman 1984. But, unlike with Netflix’s two minute standard or its easily calculable marketing spend per subscriber, we do not know which shows or movies were key to driving growth at HBO Max in Q4.

Transparency on the creative side

In that light, I thought it was unusual when Wonder Woman 1984 star Gal Gadot tweeted the Nielsen data about the success of Wonder Woman.

This is amazing! ❤ Thank you all #WW84 @WonderWomanFilm @hbomax pic.twitter.com/RM892nfJte

— Gal Gadot (@GalGadot) January 29, 2021

First, because she is not sharing data given to her by either Nielsen or HBO Max - it is a link to a Hollywood Reporter article. Second, WarnerMedia still has not shared any viewing data about the movie or any of its shows, like recent Golden Globe nominee The Flight Attendant. So as much as the tweet communicated Wonder Woman 1984’s success in the U.S., it also reflected the lack of transparency with creatives at WarnerMedia.

It contrasts with Priyanka Chopra’s tweet this week, sharing data about her film drama, The White Tiger, on Netflix.

It’s so emotional for me to see the discovery and acceptance of this brilliant incredible story. #TheWhiteTiger being embraced by audiences all over the world is awe inspiring. (1/2) pic.twitter.com/NJxln1jOBM

— PRIYANKA (@priyankachopra) February 5, 2021

Gadot tweeted Nielsen data, which is U.S.-only and typically does not measure HBO Max viewership. HBO Max shared nothing with either her or director Patty Jenkins. Meanwhile, Chopra tweeted Netflix data, which is typically shared only by Netflix corporate PR (i.e,, Shondaland productions did not share Bridgerton data, that was a Netflix press release).

The question of how much streaming data is shared with creatives varies from service to service. Because as Producer Jason Blum said above, typically creative talent gets paid upfront and gets no data. Netflix has set the market standard because it produces the most content (2,700 hours of original programming in 2020, alone). Also, most Netflix contracts do not have contractual conditions for higher payment based on performance, though the major ones (Murphy, Barris, Rhimes) do . The same is true at ViacomCBS (Tyler Perry at BET+, and recently Taylor Sheridan, co-creator/Executive Producer of Yellowstone).

Blum suggests the upside is more creative freedom, but the downside is opacity and a lack of understanding about performance. There are three comments in particular worth highlighting. First, Blum's message to Silicon Valley:

Please do not try to apply data to the creative process of TV and filmmaking. Using data to decide which films to greenlight tends to create worse outcomes. You’ll never create Get Out from a formula.

He adds:

Netflix is good at lots of things using data, but I don’t think they are great pickers.

Comedian BJ Novak, also on the call, contributed this take as a creator:

“Ambient TV” is a devastating phrase for people like me making TV shows. It implies that the show doesn’t deeply resonate and engage emotionally with the audience.

In other words, Blum’s and Novak’s bias is against the data, and are highlighting how and why the data-driven approach has limits with creatives. Which is another way of saying, the data is helpful but misrepresents the value of what they do. In turns, that implies if creatives do not value the data, then streamers have less reason to share it with them.

Netflix is driving less transparency with creatives, while creatives are showing less desire or need for data. A lack of transparency in streaming can be explained as much by cultural and business differences between creatives and technologists as it can be by the self-interest of streaming services.

Transparency in streaming is evolving in surprsing ways.

The Emerging Tension between Transparency vs Opacity

Streamers not sharing data with creatives is not anything new to the marketplace. Nor is is it new that creatives are openly unhappy with the data (Blum, Novak) or the economics (I wrote about Blumhouse's take on streaming economics last September).

Instead, the point is that transparency for investors is obviously increasing as we get signals from creatives that transparency in Hollywood is decreasing. This is happening partially because Netflix is driving the story around transparency for the marketplace, partially because of creatives, but also because other services are beginning to improve their streaming business narratives for investors with data while sharing less data with creators.

From an objective perspective, the data helps to tell a story of scale. From a subjective perspective like Blum’s, data drives his business model towards lower margins, lower quality of content, and lower returns than from the theatrical model.

This suggests that even with more transparency about the data for investors will have its limits, that lens may not capture the challenges of data with creatives in the streaming marketplace.

Disney+ and WandaVision

Disney+ has been fascinating here because it has been transparent with its data and its relationship with creators is completely different.

I think Disney+’s rollout of WandaVision offer an interesting lens on this tension. I have no idea how WandaVision is performing given mixed signals - IMDb reviews seem unusually high (41K reviews at 8.0/10) but social chatter seems minimal, except for leaks (which never happened with The Mandalorian). The Disney press push has seemed unusually aggressive relative to The Mandalorian (which got more social chatter), and an interview with Wanda actress Elizabeth Olson promised big cameos in the show (there was a surprising one last week). But also, Disney PR seems to be working unusually hard to manage the media narrative for WandaVision, particularly given that no one teased the Luke Skywalker appearance in The Mandalorian. Notably, Disney has not released any numbers for this series or The Mandalorian.

.An interview with show runner Jac Schaeffer said on a podcast (Top 5 TV, starting at 41:25) shed valuable light on how and why a different dynamic with creators is playing out at Disney. Data is less related to renewal or success, and more towards an outcome tied to another streaming or theatrical property they are engineering towards..

First, there is a larger roadmap for the show in the universe: “Kevin and executives at Marvel… always want each property to stand on its own two feet [despite vision]… and also have the pieces that need interconnect.” In other words, the creative begins with Marvel boss Kevin Feige and his team's vision for the next phase of the MCU, and where the story needs to end up at the end of a series season, or at the end of a movie. But, within the constraints of that framework, show-runners and screenwriters like Schaeffer have “a lot of prescribed freedom in my own sandbox”. As Schaeffer tells the podcast hosts, “to feel like you’re an important piece of a larger puzzle is exciting.”

Second, Schaeffer notes that the framework, and the writing processes around it, leave room for course correction both within the series and across other MCU series: “Kevin is always leaving space for is a better idea, but that space that is left is also for course correcting, should that need to happen.” To me, this reads like there are two implications: first, sData has a role, showrunners and screenwriters have access to it, but not a fundamental role in the creative process.

Disney+’s story for investors has been subscription growth. But they have not shared data on show consumption.Unlike at other streamers, data has a defined role in its creative strategy, helping to correct the narrative where necessary. With Feige taking both a central role for Marvel and Star Wars going forward, creatives at Disney will have a clearer picture of the value of data to their storytelling and success than anywhere else.

In turn, that creates a strong business rationale for Disney to be opaque with investors about show performance - creatives are getting this data from the company already, and iteratively improving the content based on it. Investors may prefer a simpler story of the best possible execution against an existing roadmap towards a 10-year plan for the MCU.

Conclusion

More media companies offering more streaming data to investors moves legacy media companies away from Curse of the Mogul-type issues (which in many ways they were moving away from already). But in not sharing performance data about particular content, we find ourselves in mirror universe Curse of the Mogul, where investors have transparency into the performance of the business but content creators know less and less about the performance of their content and receive returns for their work. Maybe this can be called an emerging Curse of the Streaming Creator - whatever it is, it is a dynamic that is shaping up to hurt creators more than help them.

Because the essence of Jason Blum’s complaint, above, is effectively, “I may know more about how a service is scaling than I do about the value of my content to consumers”. BJ Novak’s point about “ambient TV” is the kicker here: he is effectively saying because of the demand for this type of content, he feels disincentivized to create more content.

We are in the early stages of it emerging, being driven primarily by Netflix, but also by HBO Max and Starz. Disney has a fascinating dynamic given its move to have Kevin Feige control the story structure process for its IP (and we know little about Pixar or animated movies).

Last, returning to Amazon, Prime Video produces a lot of content but shares little to no data (we know Borat 2 performed well from Nielsen, but that is for the U.S. only, and Amazon Prime Video is in 200+ countries and territories). But, its channels service delivers data to studios, independent filmmakers and streaming services who use it for distribution. So they have information on how their content is performing on the service, and why they are being paid.

In 2021, Amazon Prime Video seems to be the lone streaming service that seems to feel little to no obligation about disclosing its data to investors, but is disclosing data to studios and streaming services which distribute on the platform.