Member Mailing #262: HBO Max's AVOD, DotDash, and Unlocking Value Through Fewer Ads

The surprising reasons why WarnerMedia may be imitating About.com's pivot to Dotdash for its HBO Max AVOD

[Author’s Note: Re-sending with the correct Member Mailing # to avoid any confusion in your inboxes]

Key Takeaways

The details of HBO Max AVOD from WarnerMedia executives read a lot like how IAC executives describe the pivot of About.com into DotDash.com

This strategy is focused on making the user experience more efficient, minimizing ad load, and improving ad targeting

Hulu is most analogous to the HBO Max AVOD, and has market-leading ARPU at $13.51 - an average of 1/3 ad-free tier ($11.99) and two-thirds ad-supported tier ($14.26)

A Dotdash-type strategy of minimizing ad load could lead to a higher ARPU from ads on HBO Max AVOD than Hulu’s estimated $14.26, making a total ARPU (subscription + advertising) for an HBO Max AVOD ARPU closer to $18 at launch.

Even if WarnerMedia’s strategy does not map one-to-one to Dotdash’s, the similarities help to flesh out the reasons WarnerMedia seems to be pursuing a contrarian strategy with its HBO Max AVOD.

Some key revelations emerged over the past week about HBO Max’s AVOD from AT&T and WarnerMedia executives. The first big revelation was the price: the HBO Max AVOD tier will be priced at $9.99 per month.

That prices the AVOD service $4/month above Disney’s Hulu with ads at $5.99 per month, and $5/month above both ViacomCBS’s Paramount+ and NBCUniversal’s Peacock Premium ad-supported tier at $4.99.

The second revelation was about its plans for serving ads on HBO Max AVOD, via an interview with WarnerMedia’s EVP & GM for Direct-to-Consumer Andy Forssell:

The biggest thing is there are completely new teams to kind of do this type of advertising at a high level where all the content that comes into the platform now has to have ad breaks. We didn’t need ad breaks before. [Ed. note: HBO programming will not carry advertising.] That’s a simple thing to say, but actually takes a lot of sophistication to do efficiently. You can throw humans at it and spend a lot of money but we’re trying to use technology smartly, so we’ve had to build all that capability.

And then you know, there’s a bunch of operational and technical things you have to build and policy on top of it to say, ‘How many times should we show a given user a single ad?’ That seems like a basic question but it actually sets up a really good debate internally and our answer is going to be much fewer times than many other people have decided. That means you have to turn away revenue and say, ‘We’re going to have a really premium user experience here, which means you’re not going to see ads multiple times. You might see it twice in a week.’ So, we’ve had to develop all that. It’s not rocket science but it’s got to be really thought through, especially in terms of how we look and feel different than other providers.

I have seen some interpret this quote as “he is describing lower ad load, which every other AVOD is doing, nothing new in this interview”. Perhaps it is.

But, to me, reading phrases like "much fewer times than many other people have decided” and “That means you have to turn away revenue” reads a lot like how IAC executives describe the pivot of About.com into DotDash.com. That pivot was a bet on simplicity and building a user experience for a wider audience on Dotdash websites after an over-reliance on the About.com brand had been failing.

This short excerpt from an Adweek podcast interview with DotDash CEO Neil Vogel (registration required) from July 2019 reflects the similarity:

Unapologetically, Vogel said About.com “sucked,” and as the Dotdash team thought about how to create a more useful online explainer, they decided to “only build sites we wanted to use.” To Dotdash, that meant fewer ads—no pop-ups, no interstitial—and creating content that’s actually helpful.

“We’re in the service of users, not advertisers,” Vogel said. “We care deeply about advertisers, but we have to do it on our terms.”

Part of resetting that mindset meant telling IAC, the company that owns Dotdash, that the brand will make less money than before while ramping up spending on writers. It also meant Dotdash wouldn’t chase algorithms and advertisers; instead, the company focused on creating good content and letting users find them as opposed to relying on social media or search engines.

With this risky strategy, Dotdash became the exception in the digital media publishing market, growing to 100MM+ monthly unique visitors while other big names from the past decade are shrinking (Refinery29, Vice Media). Its Q4 revenues have increased 33% YoY to $74.2 million in Q4, “the highest growth of the year while posting record profits and margins (operating income increased 86% to $28.4 million and Adjusted EBITDA increased 81% to $30.9 million)”.

It ended 2020 with $213.8MM in revenues (+28% YoY), Operating income of $50.2MM (+73%), and adjusted EBITDA of $66.2MM (+40% YoY). Advertising revenues were up 8.8% YoY, and Performance Marketing revenues were up over 85%. Before the pivot to Dotdash in 2013, About.com had “missed [its] target numbers for nine straight quarters”.

Andy Forssell’s description of WarnerMedia’s vision for HBO Max AVOD mirrors key elements of DotDash.com’s relaunch strategy:

taking big risks with the backing of a well-funded owner (Dotdash with IAC, HBO Max with AT&T)

launching with a different look and feel than competitors with fewer ads for users

being open to turning away advertisers to make less money and optimize the user experience in the short-term,

building out a sophisticated use of data-driven decision-making (Dotdash with search data, HBO Max with on-platform and off-platform engagement data)

focusing on surfacing evergreen library (Dotdash with evergreen About.com articles, HBO Max with evergreen WarnerMedia titles); and

engaging and converting users via algorithmic targeting (Dotdash converting off-platform via search engine optimization, and HBO Max AVOD converting on-and off-platform via “engagement marketing” and “significantly more personalization and better use of data across the board”).

Beyond these key similarities, it is concededly an apples-to-oranges comparison of an ad-supported streaming service that relies on pre-rolls and subscriptions, and an ad-supported website that relies on display ads and search traffic.

That said, they both share a key strategic rationale: an objective to drive higher ad revenues with less ad inventory and a less intrusive user experience. Leveraging the Dotdash lens on the HBO Max AVOD helps us to tease out both the surprising reasons why WarnerMedia may be imitating key elements of Dotdash’s strategy, and the risks in pursuing that strategy.

Dotdash, HBO Max, and Fewer Ads

Dotdash has two sources of revenue:

Display Advertising Revenue (revenue via direct-sold and programmatic exchanges), and

Performance Marketing Revenue (affiliate commerce and performance marketing commissions generated when consumers are directed from Dotdash properties to third-party properties)

HBO Max AVOD will have two sources of revenue:

Video Advertising Revenue (revenue via direct sold inventory and programmatic exchanges), and

Subscription Revenue ($9.99/month fee)

So, for Dotdash, “fewer ads” means two-thirds fewer ads than competitors, which means minimal ad placements on the page and eliminating interruptive pop-up and interstitial display ads.

For HBO Max AVOD, “fewer ads” means a market minimum of videos served per hour, both in terms of minutes and frequency of each ad. The current market minimum ad load in AVOD is owned by Peacock at less than five minutes per hour. By comparison, Hulu shows roughly nine minutes or less of commercials per hour on its $5.99 ad-supported subscription; Tubi, which is free, shows about four minutes of ads per hour; and, traditional TV networks show an average of 11 minutes of commercials per hour (and as high as 17 minutes per hour).1

For Dotdash, the objective of less interruptive ads had clearer objectives of improving webpages loading at “lightning speed”, higher on-site engagement, and ad targeting.

It is less obvious to map on-site engagement to the passive behavior of streaming video. That said, Andy Forssell laid out a broadly similar objective of serving ads “much fewer times than many other people have decided” to improve audience engagement. But it is not yet clear what advantages fewer ads than Peacock’s five minute minimum market standard offers.

HBO Max AVOD Pricing Model

Subscription revenues are another key, obvious difference between the HBO Max AVOD revenue model and Dotdash’s revenue model. Dotdash’s model is, at its core, a model driven by more variable ad revenues.

The HBO Max AVOD’s $9.99/month per user subscription fee is effectively a fixed source of revenues - meaning, WarnerMedia can expect $9.99 per subscriber. But its ad revenues are less predictable, and therefore variable.

It is worth more closely looking at each revenue stream, particularly given how the subscription revenues impact the ad revenues in ways related to the AVOD’s ability to scale.

(1) $9.99/month fee

WarnerMedia CEO Jason Kilar offered an interesting answer to a question about pricing the HBO Max AVOD monthly subscription fee at the Morgan Stanley Technology, Media and Telecom Conference in March (emphasis in bold added):

But with regards to advertising, I get so excited about it because if you start from the fan and you literally just think what can I do to help serve them better and innovate and help solve problems for them, one of the things that advertising can do, if you're thoughtful about it and you're elegant about it and you're personalized about it, you can actually do something that's very helpful for them in terms of the advertising message that you serve. And then most importantly, you're able to reduce the price for a consumer. And it turns out that most people on this planet are not wealthy. And so if we can wake up and use price and be able to kind of invent and do things elegantly through advertising to reduce the price of a service, I think that's a fantastic thing for fans.

In the portion in bold, Kilar is arguing a lower price point increases the Total Addressable Market (TAM). This also reflects a point that AT&T CEO John Stankey fleshed out a little more in their Q1 2021 earnings call:

And while we believe HBO Max without commercial interruption is a premium product and works, what we charge in the market today, we know that that premium in some cases is high enough that there are people when they start to say, well, I've got three services and I aggregate everything up that maybe I won't make a choice to be in it. And that's particularly true if you look at maybe some younger demographics. And as a result of that, we believe getting the price point down where for them to get some well-executed advertising, they would look at the product and service and say within the portfolio the streaming services that they may wish to have in their household or in their apartment that they think that this is a good place to be. You -- another example will be in certain socioeconomic dynamics.

Both Kilar and Stankey are arguing a lower price point can capture broader socioeconomic - and more importantly younger - demographics who are making “portfolio decisions of multiple services in a household”.2

But Kilar is also conceding there is some risk to the execution: they are making a bet on a perceived understanding of their target customer, which they still will need to prove out. This concession points to how a $9.99 price point brings with it four noteworthy risks.

1. The price is too high

First, there is the risk that the $9.99 price may be too high for broader socioeconomic and younger audiences. The risk is HBO Max AVOD “prices themselves out of that AVOD target audience”.

Peacock is a helpful reference for this point. We learned last week from Comcast that roughly one-third of its 42MM accounts are Monthly Active Accounts (MAAs) - meaning, “a household that pays a quarterly subscription fee or somebody who uses it monthly”, according to NBCU CEO Jeff Shell. This confirmed past reporting from The Information’s Jessica Toonkel, who shared similar data.

If we use that reporting as an additional reference, Peacock now has 14.3MM MAAs (34.2% of registered users) and only 4% use the highest-priced tier at $9.99 (570K to 1.68MM). So, it could be argued that Peacock is showing current market demand for an ad-free tier priced at a $9.99 price point is low, and that may reflect challenges for HBO Max with the $9.99 price point for an ad-supported tier.3

But, a $9.99 price point is also more likely to broaden the international customer base than a $14.99 price point for the SVOD, which will make HBO Max one of the most expensive subscription streaming services on the international market. The AVOD will be launching in 39 additional markets to the U.S. next month, and will be in another 21 markets by the second half of 2021.4

2. A risk of consumers downgrading from HBO Max

Second, given that the HBO library will not have ads served to it, “a savvy HBO fan [could] convert down from the $15 premium membership”. In doing so, those users would lose access to day-and-date theatrical releases, and would be forced to watch ads with content exclusive to HBO Max. At $5 less per month, they may not care.

In turn that would create a risk of upsetting Pay-TV distributors like Charter and Comcast who share anywhere from 30%-60% of revenue with HBO for linear subscriptions sold at $14.99/month, depending on size. This issue already played out in WarnerMedia’s negotiations with Amazon and with Roku, and resulted in ugly public standoffs of up to eight months until both deals were reached (and the Amazon deal required a separate deal with AWS). That said, Alex Sherman of CNBC reports :

“Most distributors are prepared to accept the product at its $9.99 price and market it to non-HBO subscribers and broadband-only customers”.

3. A Value Proposition Design Risk

Third, and last, AT&T CEO John Stankey also told investors last week that Prepaid wireless customers are part of the target customer base for the HBO Max AVOD:

…we believe the AVOD product actually pairs well with some of our prepaid offers and how we might position it, because it tends to line up on a more price-sensitive, socioeconomic dynamic. And we think that opens up marketing channel and awareness channel, and ultimately an opportunity to drive penetration in -- in other places where, again, customers are a bit more price-sensitive. So, it really at the end of the day, customer gets to make a choice. And there is no question if you get a lower price point you're going to push it down lower in the demos that -- that it will ultimately subscribe to it.

AT&T reported 18.4MM Prepaid wireless customers in Q1 2021, about 24% of its Postpaid customer base.

I think there are reasonable questions to be asked about whether a Prepaid mobile customer who refuses to pay a monthly fee for a smartphone will be a customer who will pay $9.99/month for a streaming service. On its face, there seems to be obvious friction in mapping the value proposition to the customer, even if there are 18MM existing Prepaid customers (and a likely even longer list of already churned-out Prepaid customers).

There are also reasonable questions to be asked about Stankey’s assumption that AT&T’s ecosystem of wireless, fiber and TV customers can provide a valuable conversion funnel for AVOD subscribers. It is especially worth asking this question given that Domestic HBO Max and HBO Subscribers - which excludes Retail (Direct-to-Consumer) but includes both linear subscribers and subscribers within the AT&T ecosystem - have remained flat at around 34.5MM over the past three quarters (as I wrote last Monday).

(2) Advertising & $14.99 Target ARPU

With the HBO Max AVOD at a price point $5 lower than the HBO Max SVOD, advertising will have to make up for the difference in lost ARPU. Again, WarnerMedia “hopes to deliver average revenue per user at close to $14.99, if not higher” for its AVOD. That means it will have to deliver up to $5 of additional effective ARPU in ads per user.

Peacock is again a helpful reference point here, as NBCU estimated at launch an ARPU per month of $6 to $7. However, that ARPU was an average across its three tiers, and not for its ad-supported tier alone. For Peacock to boost its ARPU, “either advertising rates or ad load will have to increase, or subscription prices will have to go up.”

With this in mind, the strategy for the AVOD model seems to be to boost advertising rates by serving limited ad inventory with targeting against WarnerMedia’s premium library of movies and HBO Max shows. The assumption appears to be that less HBO Max AVOD inventory will be worth more to advertisers than any other AVOD’s library, including Hulu. In turn, that will result in higher CPMs from the marketplace ($50+ and growing with demand) than those other AVOD services may get.

Hulu is another helpful reference point here, especially as to why Kilar and Forssell seem confident about this bet on HBO Max’s AVOD. Hulu reported an ARPU of $13.51 in fiscal Q1 2021 across 35.4MM subs, despite having a high ad load per hour (nine minutes or less of commercials per hour, above). Assuming two-thirds of its audience chose the ad-supported $5.99 per month offering, which they did in fiscal Q1 2020, it implies Hulu generated $14.26 ARPU off its AVOD tier in Q1 2021, alone.5 Less the $5.99 subscription fee, that is $8.27 in monthly ARPU per customer, or 20% higher than Peacock’s monthly ARPU.

If Forssell is not exaggerating about delivering a lower ad load than Peacock or Hulu, we should expect HBO Max’s AVOD to have a higher ARPU from a lower ad load than Hulu’s $8.27 at a higher ad load.

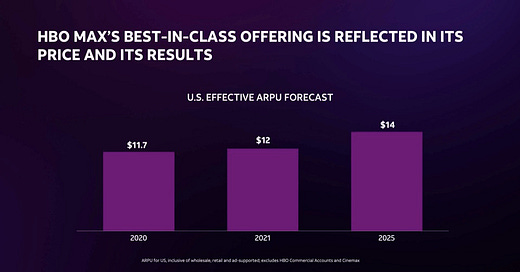

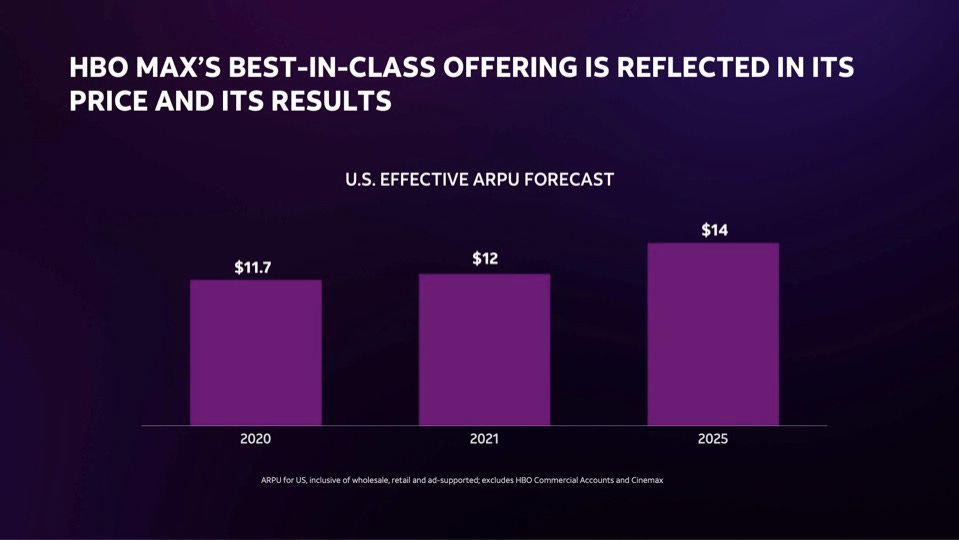

That approach would put the total ARPU for HBO Max AVOD closer to $18 at launch, or 1.6x its SVOD’s current ARPU of $11.26 and 1.5x its projected ARPU for 2021 of $12. Assuming the HBO Max AVOD ends up performing better than expectations, HBO Max’s 2025 prediction of $14 ARPU in the U.S. could be overly conservative. This AVOD ARPU math may best explain why HBO Max is pursuing an AVOD alongside its existing SVOD at a higher price point.

We will learn more about the details and positioning of this pitch at Upfronts on May 19, when WarnerMedia presents.6

Comparing & Contrasting HBO Max & Dotdash

Dotdash maximized user engagement by focusing on the best possible answers to users’ questions, with the fastest possible user experience, and loading the fewest possible ads against that. This must-read piece on how CEO Neil Vogel “blew up” the About.com business to pivot to Dotdash helps us to better understand how they did this:

While most digital media companies at the time were focusing on producing fun, newsy content to attract readers, Vogel decided his sites would focus on straightforward, service-oriented articles written by experts that readers would find helpful today or in 10 years. The websites would also load at “lightning speed” and have two-thirds fewer ads than competitors to improve user experience, thereby increasing the engagement and size of the audience—making it that much more attractive and valuable to advertisers.

Dotdash also focused on the best possible targeting for advertisers:

The clearest indicator of Vogel’s success is that advertisers seem to approve. For eight straight quarters, 18 of the company’s top 20 advertisers have returned.

Vogel says that is because the company knows exactly what people are reading, so he can target ads to them. “If you are a gluten-free food company, and you want to advertise your new pasta, we can put it on all of our recipes for pasta and all our posts about celiac disease and all of our articles about health trends,” he says. “That is way better than putting it on a random website.”

Like Neil Vogel’s 2013 prediction for Dotdash, WarnerMedia CEO Jason Kilar predicts HBO Max AVOD users will be “excited about how we've been so thoughtful about the insertion of advertising and how it's a very organic nature of the experience”.

Also, like Dotdash, WarnerMedia is willing to turn away advertiser dollars with the hope that top advertisers will be convinced to return quarter-to-quarter, and the demand for limited inventory will drive up the ARPU for ad revenues.

That said, there is an important disconnect in the comparison worth highlighting: how each business defines the target customer. Dotdash focused narrowly on a target customer: audiences who use search to answer questions. To serve that audience, Dotdash took the “strongest content”, divided it into websites that focused on one topic like health or tech, and then created entirely new brands for each website. Those websites would serve those pre-existing audiences who were already coming to About.com, and the Total Addressable Audience would grow through improved SEO.

By comparison, it is not clear as to who the target customer for the HBO Max AVOD is, or how an AVOD serves them. If it is 18MM existing AT&T Prepaid customers who could pay for HBO Max at a lower price, they currently are not paying for the service right now and it is not clear what will change their behavior.

As I wrote last Monday in Member Mailing #46, there remain around 34.5MM Domestic HBO Max and HBO Subscribers after we subtract Retail subscribers from Total subscribers from Q1 2021 numbers. That number has stayed consistent over the past three quarters, which reflects some weakness in the assumptions of the AT&T ecosystem as a conversion funnel.

If it is “younger demographics” who might pay for HBO Max at a lower price, there is no evidence those demographics exist within the HBO Max ecosystem currently. Converting them is a digital marketing challenge, one which SEO solves for Dotdash on the web better and more cost-effectively (search traffic is free) than digital and social marketing will solve for HBO Max growth in streaming.

In short, it is not clear the customer for the HBO Max AVOD exists within the AT&T ecosystem yet. Even with minimized ad load, an ad-supported model requires scale, and with the Dotdash comparison, it becomes less clear how HBO Max AVOD will scale.7

Conclusion

We are witnessing the nascent stages of WarnerMedia’s bet on an HBO Max AVOD. But, the question is where it is headed. The comparison to Dotdash has some basis in some basic similarities in strategy: WarnerMedia has a Dotdash-like focus on minimizing ad load on its HBO Max AVOD to improve user engagement for a wider audience. There are both some promising signals in this approach and some problematic signals.

The promising signals look like the drivers of Hulu’s $14.26 ARPU could lead to an $18 or higher ARPU on HBO Max with different, perhaps better offerings. But there are also some tangible risks to the HBO Max business, both in the pricing at $9.99, and in pursuing a lower ad load than the competition before scale has been achieved. Without that pre-existing scale, there is the risk of cannibalizing the existing HBO and HBO Max user bases at $14.99 for a lower price point and lower ARPU.

That is unless the existing user base of 44.1MM HBO and HBO Max subscribers is the target customer base. Because, if WarnerMedia’s bet is the HBO Max AVOD is more likely to succeed than the SVOD, then WarnerMedia believes HBO Max may not be able to scale at its $14.99 price point, and linear HBO is likely to lose subscribers due to cord-cutting.

With an HBO Max AVOD service, there may be no downside to anticipation the risk of consumers downgrading from HBO or HBO Max. It is not unreasonable to go one step further and foresee the HBO SVOD tier becoming something analogous to Disney+’s $30 premier access tier for theatrical releases.

Even if WarnerMedia’s strategy does not map one-to-one to Dotdash’s, the similarity in the minimalist simplicity of the approach helps to flesh out why WarnerMedia seems to be pursuing a contrarian strategy with its HBO Max AVOD.

As I wrote last January in “Member Mailing #188: Peacock is targeting too many customers to succeed”, Procter & Gamble Chief Brand Officer Marc Pritchard was a big reason for Peacock’s market low ad load of five minutes. As this AdAge article explained about why Pritchard was excited for Quibi:

It all amounts to what Pritchard has been seeking for years from his bully pulpit as chief marketer of the world’s biggest advertiser (once again) and chairman of the Association of National Advertisers: content that appeals to millennials and younger, but with old-school production, business and editorial values—brand-safe, with minimal clutter and verified audiences.

Kilar also seems to imply that advertising may help them to reduce the price below $9.99: Alex Sherman of CNBC reported “WarnerMedia had preliminarily considered selling an advertising-supported product of just HBO Max content for $4.99 per month, but nixed that idea”. So Kilar and WarnerMedia management seem to be aware know their target customers are price-sensitive.

It is also worth noting that Hulu has 36MM+ subscribers at a lower price point ($5.99 per month), and its growth had been flat for a few years until it was acquired by Disney and integrated into a Disney+ bundle. Since 2019, it has grown its user base by almost 30%.

Notably, Comcast is suggesting that Peacock will launch internationally, too.

The math is: $13.52 = [.33*(5.99)] + [.67(x)]

$13.52 = $3.96 + .67x

$9.55=.67x

x= $14.26

Notably, Forssell does not mention Xandr in his interview, only Turner’s ad sales and ad ops capabilities. Xandr is a division of WarnerMedia that was originally built out to deliver the type of sophisticated addressable and innovative ad serving operations that Forssell is describing, as this 2018 profile of former Xandr CEO Brian Lesser lays out. HBO Max appears to be building its ad delivery solution from scratch.

But with Upfronts looming, there remains an interesting question of how Turner’s ad sales team will sell HBO Max inventory for the first time, and selling new addressable and innovative advertising solutions that are less interruptive.

On this point, I also wonder whether the AVOD will be a mostly international product, and that is how it will scale. Forssell implies as much to Deadline:

The development team was also doing a bunch of work because we’re launching in Latin America. So, they’re having to build a bunch of capabilities due to multi-language and multi-currency and a lot more.

But international requires product channel fit within each country, which is a costly marketing problem for which HBO Max’s AVOD will need to solve.