Member Mailing #262: Roku, YouTube & Product Channel Fit

Neither Roku nor YouTube is incentivized to cooperate, but they *need* each other to succeed in Connected TV

Key Takeaways

Google’s demands in its negotiations with Roku suggest Google is trying to mold the Roku’s hardware to its product needs, specifically its AV1 codec

This would suggest Roku has vulnerabilities that Google is trying to exploit with “anticompetitive behavior”

The Co-opetition framework (Monday AM Briefing #47) suggested Roku and Google were not incentivized to work with each other

But, surprisingly, the Product Channel Fit framework reveals just how much Roku and YouTube need each other in the Connected TV marketplace.

“Products are built to fit with channels. Channels do not mold to products.”

The ugly Roku-Google standoff reached a new phase last Friday, when YouTube announced it was adding a “Go to YouTube TV” workaround within the main YouTube app for YouTube TV bundle subscribers on Roku. Roku responded by calling Google’s actions “the clear conduct of an unchecked monopolist”.

This move by Google reminded me of my favorite quote about Product Channel fit, above.

In Product Channel fit terms, YouTube rebuilt its YouTube product to keep Product Channel fit on Roku for its YouTube TV service. But, looking back on what I wrote last Monday, it also seems to be that Google is trying to mold the Roku channel to its products, and as above, “channels do not mold to products”:

Roku is particularly unhappy that Google has been leveraging the negotiations to force an upgrade to the AV1 codec, an open-source video codec that promises better-looking 4K videos at lower bitrates (basically, more efficient streaming). Roku is telling the marketplace that it is not incentivized to pass on to consumers the additional costs that the AV1 codec would require, but it would be more incentivized to do so if Google would agree to change the terms of its separate YouTube deal with Roku.

Google is saying it is not incentivized to revisit those terms.

Google has turned a feature request for the Roku product - the AV1 codec - into a strong-armed negotiation tactic, and with the contrarian objective of forcing the channel to adapt to the product.

I think it is worth focusing on how heavily Google is leaning into Roku in this negotiation. Because it either reflects Roku’s vulnerability as a channel for distribution, or it reflects the strength of Roku’s position as a necessary channel for streaming distribution. There is evidence for both.

At a time when YouTube is becoming the most dominant connected TV behavior next to Netflix, it raises the question of the extent to which Google needs Roku, and to which Roku needs Google.

Roku & Product Channel Fit

I have found Product Channel Fit to be most valuable as a way to compare distribution strategies. Understanding where a streaming service is not being distributed is as valuable as seeing where it is being distributed.

Roku has proven itself to be a necessary channel for every streaming service, and its 53.6MM active accounts reflect this reality.

The only question of product channel fit is whether a service will accept terms for being distributed within Roku’s Channel Store (a percentage of subscription and/or advertising inventory) or as a Premium Channel add-on within The Roku Channel. It is Roku’s preference that a service is distributed as a Premium Channel add-on through The Roku Channel, because that model allows it to capture more of the economics and more user data.

In some ways, the Premium Channel model is a marketing partnership that reflects the “win-win” relationship Roku promises its partners, as Roku EVP Scott Rosenberg describes it:

So the best, winning recipe is a model, an economic relationship between the parties where we’re both winning, we’re both earning as we drive the success of these apps. That’s what we seek and ultimately, in some cases, it takes us a little longer to get there with the parties

For smaller services like AMC+, discovery+, Starz, and Paramount+, the Premium Channel model has worked better. Roku has highlighted promotional campaigns from Premium Channel partners discovery+, Starz, and Paramount+ in recent quarters, and they have reported good metrics. But, it also has highlighted campaigns from Channel Store apps like Peacock and Disney+. “Win-win” with partners has many different objectives and many different outcomes.

YouTube & Roku’s Vulnerabilities

YouTube is available via the Channel Store on Roku. “YouTube is the second most-popular app on most smart TV platforms, closely following Netflix”, according to Protocol’s Janko Roettgers.

Although we do not know the deal terms between Google and Roku, it is an interesting question of whether YouTube allows Roku to serve ads to 30% of inventory, or if not, what percentage of inventory it granted Roku.

As Roettger’s article on the fraught YouTube-Roku relationship reflects, YouTube leverages its market size to extract concessions in exchange for this share of inventory. Roku alleges that YouTube is effectively using its market size to force concessions that could negatively affect Roku’s business, and has done so before:

Google allegedly forced Roku to add a row of YouTube search results to its universal search UI, effectively making sure that people searching for a movie always also see YouTube results with the trailer and additional videos as results.

Google’s demands around voice search is another issue in the standoff:

Google wants to force Roku to only show YouTube results when someone launches a voice search from within the YouTube app. If, for instance, someone browses YouTube and then decides to listen to music, a voice query like "Play 'Uptown Funk'" would open the song on YouTube, even if the consumer had set Pandora as their default music app.

A new Roku OS update is supposed to solve this latter problem for all Channel Partners, but it is not yet clear whether Google has agreed to it.

Even if the 30% of inventory has seemed costly for other partners - it was a key issue in the WarnerMedia and Peacock standoffs with Roku - for YouTube the “win-win” logic of those business terms has been used as an opportunity to aggressively push its business agenda. Google has had success with this heavy-handed approach in the past, and Roku appears to have a long memory.

Does This Mean Roku Is Vulnerable?

YouTube’s aggressiveness reached new levels last Friday, announcing it was implementing a workaround that will make YouTube TV available within the existing YouTube app “if (or when) Roku blocks access to the YouTube TV app.”

The move implies that Roku is vulnerable to both competitive engineering - meaning, YouTube can engineer a trojan horse of its YouTube TV service into Roku - and to YouTube’s willingness to build worse user experiences than a dedicated YouTube TV app to retain paying YouTube TV subscribers (at $64.99/month) on Roku.

But, in the first instance, Roku continues to take a share of monthly fees from YouTube TV subscribers, and in the second instance, its decision to remove YouTube TV’s app from the Channel Store has forced YouTube into a worse user experience for its users. So it is a question of what it means for YouTube to be aggressive in these negotiations and whether Roku is indeed “vulnerable”.

I think this move with YouTube TV may betray weakness on YouTube’s part: YouTube TV is a virtual MVPD, and at 3MM+ subscribers, it has 6% of Roku’s active user base. YouTube TV needs Roku to grow, and YouTube’s workaround move revealed it needs to retain consumers as much as it needs to grow the business.

In Product Channel Fit terms, YouTube molded its product to Roku’s channel to keep its customers happy… after demanding that Roku mold its channel to YouTube products. That move puts Roku in the driver’s seat, not YouTube - YouTube may make changes, but Roku still controls the access to 53.6MM active users. In this light, these vulnerabilities are more like nuisances related to a specific set of negotiations, and not fundamental threats to Roku’s distribution business.

YouTube’s AV1 Codec Pain Point

As Stratechery’s Ben Thompson wrote in yesterday’s Daily Update, “Roku's Earnings, Roku and YouTube's Streaming Ads, Roku and YouTube's Dispute”:

…from what I can see Roku is picking a fight with Google over access to YouTube TV as a pre-emptive strike over upcoming negotiations for YouTube itself, where Google wants Roku to include a higher performance chip in its devices to support a more efficient codec for YouTube videos. It makes sense that this would matter to Google: the cost of encoding YouTube videos almost certainly far exceeds the profit (if any?) that Google makes on YouTube TV, even though there is little obvious benefit to Roku, whose strategy in part depends on having the cheapest streaming devices on the market.

Through this lens, Roku seems more the aggressor, and YouTube seems more vulnerable than Roku. Not only does YouTube need distribution on Roku to scale, it also needs Roku to adopt the AV1 codec for YouTube and YouTube TV to run its YouTube businesses more profitably. YouTube needs Roku to adopt the AV1 codec to ensure a consistent 4K streaming experience for users across YouTube across all platforms.

Last Monday, through the lens of co-opetition I thought this reflected a “jiu-jitsu-type move” from YouTube to leverage its enormous scale:

…as a means of breaking Roku via Roku’s “win-win” business terms. So, in this light, Google is saying “the success of YouTube apps on Roku needs the AV1 codec, and YouTube users need a better user experience on Roku ”. Roku finds both requests problematic, but both requests are necessary for the YouTube apps succeeding within the Roku ecosystem (Roku “commanded 37% of big screen viewing time in Q1 2021”, according to Conviva’s State of Streaming Q1 2021 report).

Roku is telling the marketplace that it is not incentivized to pass on to consumers the additional costs that the AV1 codec would entail. Roku achieved Product Channel Fit because its “strategy in part depends on having the cheapest streaming devices on the market”. A key Roku storyline in Q1 was its devices are getting cheaper, with average selling prices declining by 7% YoY. YouTube’s demands around the AV1 codec would effectively kill that story.

YouTube may be a market heavyweight with U.S. connected TV (CTV) consumers - remember, last December over 120MM people in the U.S. streamed YouTube or YouTube TV on their TV screens. It is second only to Hulu in terms of Connected TV ad share at a projected 19.6% in 2021 to Roku’s 10.1%., according to eMarketer. It is projected to have just under 2x the net CTV revenues of Roku in 2021, and 1.8x in 2022.

However, without distribution on Roku, or with distribution on Roku compromised by a lack of an AV1 codec in Roku devices, YouTube’s connected TV growth is not as strong. If we conservatively assume 75% of Roku’s 53.6MM Monthly Active Users (MAUs) have downloaded the YouTube app, there are just over 40MM MAUs of YouTube on Roku. Any complications or friction in the YouTube experience may reduce engagement on the YouTube app.

According to Roku’s “win-win” logic, that is a lose-lose outcome for both YouTube and Roku.

Roku & YouTube Need Each Other

The eMarketer data implies both Roku and YouTube are competitors in the CTV ad marketplace, and that is objectively true. Roku acquired DSP dataxu and launched OneView ad platform to better compete with YouTube for addressable ad inventory.

However, because their inventory is programmatic - meaning, it can be bought and sold directly or via DSPs - their competition takes place in black boxes. So, the best objective measure of success we have will be total revenues on their respective platforms. But even that is not a one-to-one comparison given that YouTube has exponentially greater scale in the connected TV marketplace: Roku reported The Roku Channel reached 70MM homes in Q1, or 58% of YouTube’s reach in December, alone.

If YouTube has lower CPMs than Roku, that is because it is monetizing a longer tail of impressions across more users at lower CPMs than Roku. But, as Ben Thompson also wrote in Monday’s Daily Update:

YouTube has the edge on Roku as far as direct response marketing goes, in part because the company can better trace conversion; when it comes to brand advertising, though, both are benefitting from the decline in linear TV, augmenting their share of screen time with user data.

That said, YouTube needs Roku’s audiences to grow its Connected TV business. Engagement per account on Roku has gone up, as this chart reflects:

In Q1 2021, streaming hours on Roku went up 49% Year-over-Year (YoY) while active accounts grew 35% (YoY). So by being on Roku, YouTube both benefits from more active accounts and more engagement per account.

Roku’s Vulnerability Lies Outside The U.S.

That said, YouTube’s need for Roku as a distribution channel may be U.S.-based, only. The majority of those 53.6MM Roku active accounts are based in the U.S.

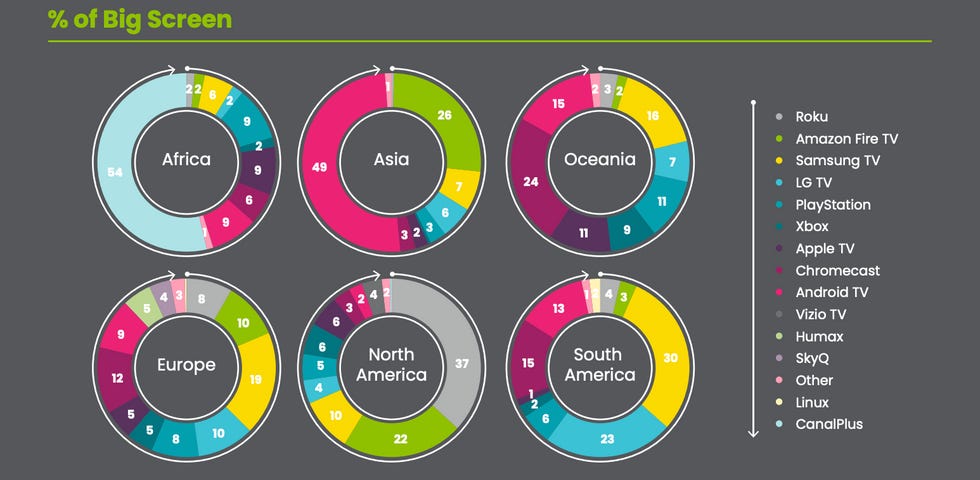

Outside the U.S., Roku does not have scale, according to Conviva’s State of Streaming Report for Q1 2021:

Roku began selling devices in Brazil last year, and has been in other Latin American countries as well as parts of Europe for a few years now. However, the company's European business didn't have much of an impact this past quarter, either, amounting [to] just 8% of all big-screen streaming.

And while streaming on TVs has been surging in overseas markets, Roku has been slower than some of its competitors to capture those eyeballs. "We are not seeing them benefit from that," said Conviva's marketing director, Paula Mantle Winkel. Roku's global share of big-screen viewing time fell from 33% in Q1 of 2020 to 30% in Q1 of 2021, according to the company's report.

It is also worth adding that Roku only owns 4% of the Latin American market.

Generally, Roku faces enormous competition in the streaming device and TV OS marketplaces internationally. Meanwhile, Google’s Chromecast OS and Android TV devices have large shares in South America, Europe, and Oceania. Android TV dominates in Asia. Google’s new Chromecast with Google TV has been getting universally positive reviews since launch.

Roku faces an uphill battle for its Player business in international markets, which impressively grew 22% YoY despite this competition. The biggest challenge is cost: how will they convince other OEMs to use their Smart TV operating software. With some of the lowest prices and variable margins (4.6% in Q4 2020, 14.8% in Q1 2021), there is little if anything they can offer in terms of a fee per device that can compete with what Google, Samsung, or Amazon can offer.

All signs point to Roku relying on its Roku Channel app to expand its ad business, which is 81% of its net revenue and 95% of its gross profits.

But, it still needs to sell players and for Smart TV manufacturers to adopt its Roku OS. That is becoming harder to accomplish with Google’s, Amazon’s, LG’s and Samsung’s existing market penetration in international markets.

This leads to the fun, if not amusing, irony of Google’s hard stance on the AV1 codec: no existing Android TVs, nor the new, well-reviewed Chromecast with Google TV, have the hardware for the AV1 decoding process. Only “Sony’s new Bravia XR lineup, which runs Google TV supports AV1 decoding [sic], as does the latest Amlogic S905X4 chip that’s being used in more streaming boxes”, according to 9to5google.

Looking at the Roku-Google negotiations in this light, Roku seems to understand the inevitable outcome that it will need to adopt the AV1 codec. However, both inside and outside the U.S., Roku feels no market pressure to make that change, yet. But market pressure appears to be the bet Google is making in the long-term.

Given that Google has yet to update the hardware of its own devices for the AV1 codec, it is even less clear what the business objectives of this negotiation seem to be on its end. There is no product channel fit for the AV1 codec anywhere, yet, and there is little to no upside for Google in messaging to customers inside the U.S. or outside the U.S. that Roku cannot provide the AV1 codec. It is an obtuse engineering problem, for now.

Conclusion

Last week I looked at the YouTube-Roku dispute through the lens of co-opetition and concluded:

…co-opetition is about two competitors both realizing that there are more incentives to cooperate than to compete. The problem here is neither company is incentivized to cooperate.

I also wondered if “Roku’s “win-win” business logic may not be the best model for working with tech giants in streaming”.

Looking at the same dispute through the lens of the Product Channel Fit framework, different conclusions emerge. The first takeaway is surprising: while the Co-opetition framework suggested that the companies were not incentivized to work with each other, the Product Channel Fit framework reveals just how much Roku and YouTube need each other in the Connected TV marketplace.

Second, Google may have miscalculated in how it is pushing for the adoption of the AV1 codec. There are obvious operating margins-related reasons why Google needs the AV1 codec for YouTube and YouTube TV streaming, but we are in the early days of streaming hardware being able to support that codec. There is no immediate need for Roku to support it, especially given the risk of higher costs for users after its prices fell YoY near 10%.

Last, Roku may seem vulnerable because of the moves that YouTube has made in the past and with its YouTube TV workaround. But, both YouTube and YouTube TV need distribution on Roku in the U.S. More importantly, YouTube may not need distribution on Roku anywhere else to reach the Connected TV marketplace, but it needs it in the U.S.

Roku may have vulnerabilities, but exploiting them will do little to help YouTube or Google better reach Connected TV audiences.