Member Mailing #263: The AT&T-Discovery Merger's Questionable Bet on Rebundling

The finances of the future merged company make sense, but it may take the direct-to-consumer relationship for granted

Key Takeaways

In merging with WarnerMedia, Discovery Chairman and CEO David Zaslav appears to have follow Barry Diller’s advice was to “go big” and to “own nonfiction programming and be an essential streaming service”.

With projected ~$52B in revenues, ~$15B in pretax profit, and free cash flow of $20B by 2023, the business will be robust out of the gate.

But, it risks not becoming “an essential streaming service” in the long run because Zaslav has a bias towards “merging content and distribution usually doesn’t make sense”, and therefore B2B bundling deals are better than DTC relationships

Three of PARQOR’s Five Frameworks highlight how the new business risks maximizing the decline of the linear business more than scaling towards more streaming consumers globally.

I think perhaps the best place to start a deep dive into the announced merger between Discovery and WarnerMedia is this anecdote shared in The Wall Street Journal’s report on the launch of discovery+:

[Mr. Zaslav] said Discovery made the decision to offer a comprehensive streaming service after the company surveyed consumers and found that they wanted a one-stop nonfiction streaming destination to complement the fiction-heavy Netflix and Disney+.

Late last year, Mr. Zaslav wanted a second opinion on that plan. So, he invited his old friend, media mogul Barry Diller, out for lunch. Over poached salmon and chopped salad at the Grill in Midtown Manhattan, Mr. Diller rendered his verdict: It could work. But to be successful, Discovery would have to go big.

“I told him Discovery could own nonfiction programming and be an essential streaming service—about the only one that could have a chance at competing with Netflix profitably,” Mr. Diller said in an email.

Yesterday, David Zaslav went “big” alongside his friend and occasional golfing partner AT&T CEO John Stankey, announcing a new media company that will be the second-largest media company in the world by revenue after Disney, will have a bigger library than Netflix and will have ~$52B in revenues, ~$15B in pretax profit, and free cash flow of $20B by 2023. Zaslav told CNBC he foresees the company reaching “[up to] 400 million homes over the long term”.

Barry Diller’s advice was to “go big” and to “own nonfiction programming and be an essential streaming service”. Discovery certainly went big in merging with WarnerMedia, but it now owns a lot more than nonfiction programming in both Warner Bros. and HBO:

The enlarged Discovery-WarnerMedia will have massive reach across news, sports, unscripted, lifestyle content and some of entertainment’s biggest franchises and tentpole events from the HBO and Warner Bros. imprimaturs.

Its value proposition and ambitions have expanded far beyond Diller’s guidance to focus on unscripted.

This is one reason why, as I wrote yesterday, I think the newly merged company - which some are calling WarnerDisco or DiscoMedia or even DiscoTime, but I like to call DiscoMax - is a global media behemoth for extracting maximum value out of linear as a declining business.

My key concern for DiscoMax is its marketing or Product Channel Fit strategy of rebundling, as summarized succinctly in this tweet.

WarnerMedia CEO Jason Kilar and his team actively and aggressively rejected the assumption that a DTC world necessarily evolves toward rebundling. They went as far as sitting through seven-to-eight-month standoffs with both Roku and Amazon to ensure that deal terms could be reached where WarnerMedia owned the customer relationship. But, Zaslav will be building DiscoMax with “traditional b2b deals under the assumption the digital world rebundles.”

As much as DiscoMax’s proposed business model makes sense for shareholders out of the gate, I also think it compromises both Discovery’s and WarnerMedia’s streaming ambitions globally because the assumption of rebundling involves compromising the relationship with consumers in a direct-to-consumer (DTC) world. Both discovery+ and HBO Max need scale, but it is not clear how traditional B2B deals in a DTC world help to achieve scale given that they have yet to do so for legacy media offerings, to date.

This key detail, and some additional key details teased out by three of PARQOR’s Five Frameworks, leave me skeptical this approach is going will be big in streaming.

Deal Terms & Timing

Before I jump into what we learned from the frameworks I think it is worth highlighting two notable elements of this merger that are not getting enough discussion, and which are integral to understanding DiscoMax’s strategy.

1. Deal Terms (& John Malone)

There is much to say about the challenges of this deal, but none of that can be said without first addressing its structure.

As I noted above, Discovery is bringing a business model driven almost entirely by domestic and international distribution and advertising revenues. Discovery is “the most-watched pay-TV portfolio in the U.S.” and earned 67% of its $2.79B in 2020 revenues from U.S. networks.

Given this, its focus on unscripted, and the small scale of its DTC efforts to date, a merger with WarnerMedia never seemed obvious (though a smaller merger with CNN seemed more obvious to some). Why would two legacy media businesses with newer SVOD bets in the DTC space merge to maximize the value of their linear media businesses over their streaming businesses?

So this merger has been a surprise for many in the media industry - it was never an imagined scenario by the wisdom of the crowds (as Joe Adalian writes in Vulture).

The deal terms are interesting because they are weighted more towards financial engineering, as The Hollywood Reporter explained:

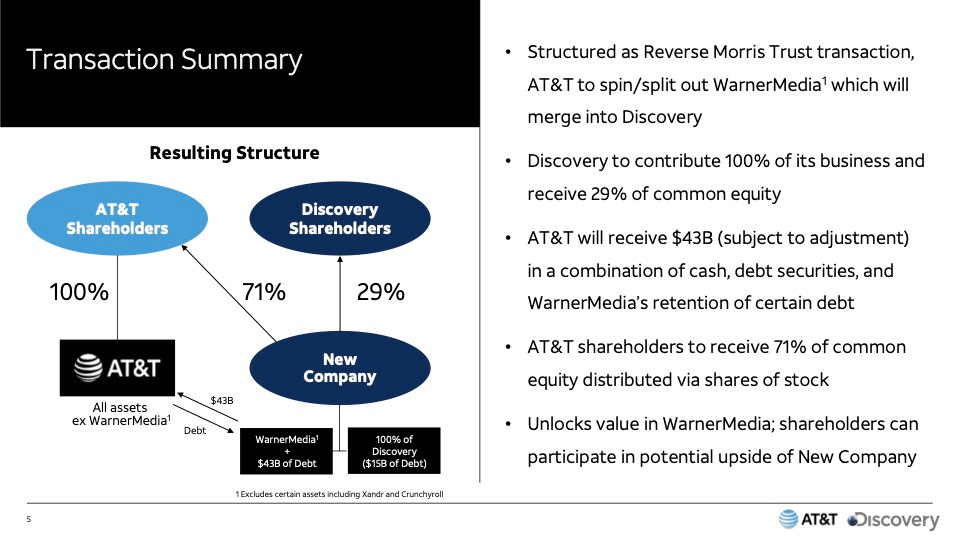

Wall Street observers said the Reverse Morris Trust bore the mark of major Discovery shareholder and media mogul John Malone, who has a reputation for complex, tax-efficient deals.

But for John Malone’s approval and his sophisticated insights into tax-efficient deals, this merger was unlikely to happen. Nor was another suitor likely to offer a business outcome for AT&T where it shed debt and got both $43B in return to reduce debt, a 71% share in the new business for shareholders, and seven board seats in DiscoMax.

I think this is an important detail given how much speculation focused on a WarnerMedia-NBCUniversal merger. I was skeptical of that merger happening because according to the PARQOR Hypothesis, the optimal outcome required the acquisition of Six Flags, too. But this Reverse Morris Trust detail implies that AT&T probably did not have compelling outcomes in front of it which also returned both $43B in cash and a majority share of the new company to its shareholders.

It is also worth noting neither Malone’s participation nor ultimate sign-off on eliminating his voting shares in Discovery to get a deal done with WarnerMedia was guaranteed. It could be argued that but for John Malone, this deal would not have been reached.

But it also could be argued that, but for John Malone, this DiscoMax would be less reliant on a linear model going forward. Zaslav seems to share Malone’s belief that “merging content and distribution usually doesn’t make sense”:

“I think that the technology of connectivity and digital technologies are one focus, and creating content that people get addicted to is another focus,” he said. “And you seldom would find both of those in the same management team.”

In other words, but for John Malone, HBO Max’s streaming strategy might have continued and Jason Kilar might have stayed for DiscoMax.

2. Timing & Pull-Forward Impact

Last month I wrote about how Netflix’s deal with Sony reflects the “pull-forward impact” of the pandemic on both Netflix (slowdown in subscribers growth and STARZ (“forcing it to have an unusually heightened focus on marketing its original series”).

The question is how the timing of the deal reflected the “pull forward impact” of the pandemic on AT&T. Stankey mentioned the term “escape velocity” a few times in this morning’s press conference announcing the deal:

I think what he was referring to was how, for the past three quarters, “Domestic HBO Max and HBO Subscribers after we subtract Retail subscribers” has been steady:

34,408 (Q3 2020)

34,648 (Q4 2020)

34,490 (Q1 2021)

The AT&T ecosystem has provided no obvious Wholesale growth for HBO over three successive quarters. Moreover in Q1 2021, it did not share an “HBO Max - Activations (Cumulative)” metric in its Q1 2021 earnings after having done so over the past year. That metric implicitly told the story of Wholesale conversion to HBO Max accounts. After Q4 2020, AT&T no longer had that story to tell.

As Variety’s Cynthia Littleton reports, this added urgency to the early discussions between Stankey and Zaslav:

…in part because Netflix and Disney released financial data indicating that their streaming platforms were growing by leaps and bounds during pandemic conditions. WarnerMedia was seeing traction with HBO Max after Warner Bros.’ movies started to land on the service day-and-date with theatrical releases.

My guess is this data was increasingly weakening the rationale for AT&T to keep WarnerMedia in-house: despite evidence that Kilar and his team were doing a great job growing the subscriber base, the business had pain points which AT&T could simply not solve for with more cash (as it did with $200MM in payouts to compensate talent impacted by day-and-date release), or with its enormous user base, or with a lower price point. HBO Max was not scaling as well as its competition had within the same time period (more on this under Fiduciary vs. Visionary, below).

Stankey added some color to this point in the Investor Conference Call in response to a question about the future of “the HBO Max relationship on an ongoing basis with wireless and broadband and the like”:

…the opportunity for David to grow this media company globally is what outstrips the value creation from us owning the asset and driving churn and customer acquisition and connectivity domestically in the U.S. and allowing him to go after a opportunity globally that's got a much bigger multiple on it.

That reads like there was a compelling business rationale, supported by data, for why AT&T saw “escape velocity” in this moment of “pull forward impact”. AT&T was witnessing in real-time that its ability to scale and create value for HBO Max was insufficient. Discovery offered a better opportunity for value creation for WarnerMedia, both outside the AT&T ecosystem and internationally.

The Five Frameworks

PARQOR’s Five Frameworks highlight both the connections and disconnects in the data and available evidence for a company’s business that you may not be seeing. The common approach to each framework is a focus on incentives and an emphasis on the Direct-to-Consumer business model logic of streaming.

Both companies leveraged the press conference and the subsequent Investor Conference Call to sell their respective streaming efforts. Zaslav upsold discovery+:

For us, we thought it was going to be mostly subscription and that we found that the light product had unbelievable ARPU for us, over $6. So we charge $5, we make over $6 and we're making $11 a subscriber, 50% more what we were making on a cable sub.

And later in the call in response to a question from Michael Nathanson, Stankey upsold how “HBO Max, on a stand-alone basis grew revenues over 30% in the first quarter.”

Stankey later added:

The last thing I want to do is hand off an asset that's not growing at the rate and pace that we want it to grow because it will be a key driver of value, and what we want to hand off and what we believe we have engineered for David, tend to pick up an entities [sic] that can grow rapidly and that we can see the equity, begin to appreciate the market because of that and our shareholders enjoy the benefit of that to the extent that they choose to stay along for the ride, which us [sic] truly will be staying along for the ride of my piece of it. In short, the positioning of the streaming assets was around high ARPU services with better international growth prospects because of a larger library. There is plenty of compelling evidence for that.

The streaming story told by both CEOs was larger library, higher ARPU, and continued growth.

The Five Frameworks tell a slightly different story1. I think the most interesting Frameworks to focus on are these three:

The PARQOR Hypothesis: what are the attributes of the DiscoMax ecosystem?

Product Channel Fit: how will DiscoMax scale?

Fiduciary vs. Visionary: Did I misread David Zaslav by labelling him a Fiduciary?

The PARQOR Hypothesis

A key reason this Member Mailing began with the anecdote of Barry Diller and David Zaslav having lunch is, as much as the DiscoMax merger is about Zaslav following Diller’s advice, it also about the irony of Zaslav not meeting the five conditions of the PARQOR Hypothesis (which is based on IAC’s rationale for investing in MGM Resorts) in doing so.

The PARQOR hypothesis argues that the streaming services most likely to succeed must meet a specific set of conditions:

An Aspirational Brand

An Existing User Base at Scale

Multiple Avenues to monetizing the same IP, and

Daily value proposition (something new for fans to consume daily)

Sales channels online (digital) and offline (physical) commerce

Looking at DiscoMax through the streaming lens only, it seems to 2.5 out of 5 on the BEADS checklist:

An Existing User Base at Scale, and

Daily value proposition (something new for fans to consume daily)

Online Sales channel, only

Discovery is not an aspirational brand: as Zaslav and his team like to emphasize, their talent and library content are more well-known than the Discovery brand. HBO Max also is not an aspirational brand, as I wrote in Member Mailing #257: The PARQOR Hypothesis Predicts Streaming in 2025.

HBO Max could be argued to be an Aspirational Brand because HBO has historically been an aspirational brand. However, it is important to remember AT&T created the Max brand with the intent of reaching a larger audience than HBO’s linear brand. Its upcoming, lower-priced HBO Max AVOD tier (June 2021) suggests WarnerMedia is trying to create expand that audience for the HBO brand, or a broader Total Addressable Market (TAM), even further with a lower price point.

Discovery does not offer multiple avenues for monetizing the same IP: it is laser-focused on the linear distribution model, and is new to streaming. It has tested additional models: the Food Network Test Kitchen, an interactive show on Amazon, is still in-play but has not scaled. As for WarnerMedia, it certainly monetizes its DC Comics and Warner Bros library via licensing deals to Six Flags, Universal Theme Parks and Studios, and merchandisers. But it is not like Disney in that approach, mining that IP to exploit it across movies, TV shows, merchandise, and theme parks.

Last, Discovery has no physical commerce offerings, but HBO Max has promotional real estate in AT&T stores after the deal is closed. A key question for DiscoMax will be whether it continues as an offering on AT&T wireless and broadband plans, especially given that discovery+ has a promotional deal with Verizon. Both Stankey and Zaslav were non-committal to a continued ongoing relationship, but Stankey told investors on the call, “our intent is to continue the relationship”.

So, the logical question is, if DiscoMax does not meet the conditions of Barry Diller’s hypothesis, is this a negative?

A key point of the PARQOR Hypothesis is that 21st century media businesses need to engage consumers across multiple channels, both to succeed and to learn as much about their customers as possible. I think this was something Kilar understood unusually well (which I discuss more below): the optimal media business model is not to focus on only distribution or only content creation.2

Whereas, Zaslav seems laser-focused on linear and digital distribution with DiscoMax, the business model’s reliance almost entirely on linear revenues implies he is more focused on maximizing the value of linear more than on growing digital.

The PARQOR Hypothesis & Netflix

Funnily enough, Netflix is the only other company that scores a 2.5 out of 5 on the BEADS checklist. So, in one sense, Zaslav has achieved Diller’s recommended objective of building a version of a competitor to Netflix, reflected in its $20B of content spend per year to Netflix’s $17B.

Also, looking at numbers like ~$52B in revenues, ~$15B in pretax profit, and free cash flow of $20B by 2023, DiscoMax will come to market with an objectively “better” business model than Netflix’s highly-levered “Debtflix” model.

But, that also means my critique of Netflix as a media company applies to DiscoMax, too. Meaning, Netflix seems stuck within its digital-only distribution model, limited by its difficulties in developing a library of IP from which it can monetize in multiple ways beyond streaming.

DiscoMax will be different from Netflix only in that it will offer both linear and digital distribution for the same library of content. But otherwise, they will face fundamentally similar challenges in engaging consumers around their IP across platforms.

Product Channel Fit

HBO Max and discovery+ have taken two fundamentally different paths to achieve Product Channel Fit. Those two paths reflect a fundamental difference in philosophy between Jason Kilar and David Zaslav. As the tweet in the introduction said, Zaslav’s deal-making has focused on “traditional b2b deals under the assumption that the digital world rebundles”.

Kilar, on the other hand, was willing to have eight-month-long standoffs with both Roku and Amazon because he did not agree with the economics or data-sharing requirements of the digital world’s “rebundling” deals. In the instance of the Amazon standoff, it required a separate deal with the AWS group to reach an agreement.

In some ways, the difference between both approaches is the extent to which one believes Netflix’s model “ubiquitous access” is the paradigm. Netflix owns its relationship with consumers on-platform and pushes the limits of its marketing on third-party platforms to own that relationship off-platform, too.

Kilar believed strongly in that model, bringing in executives like Andy Forssell with experience in DTC streaming to run the DTC business and drive a better audience relationship across channels. Kilar himself engaged in a “for the fans” approach to distribution, actively engaged with audiences on social media, touring them around the Warner Bros lot, and feeding rabid fanbases with content, like Zack Snyder’s Justice League and day-and-date releases of Wonder Woman and Godzilla vs. King Kong. His team’s objective was a direct and robust relationship with the consumer across platforms with the objective to own the relationship with the consumer, and understanding as much as possible about them.

In short, Kilar and his team focused on doing everything possible to avoid rebundling. This contrasts starkly with Zaslav’s approach to Product Channel Fit of embracing revenue-sharing and data-sharing deals with the likes of Roku, Amazon, Xfinity, and other third-party platforms. Again, Zaslav seems to share Malone’s belief that “merging content and distribution usually doesn’t make sense”.

I wonder if this new approach risks alienating a lot of HBO Max consumers, both existing and target. I think it will. Like discovery+, I think DiscoMax will disappoint on streaming subscriber numbers for a while, and may not ever reach 400MM households.

Fiduciary vs. Visionary Executives

Jason Kilar has been one of my favorite examples of a visionary executive, and David Zaslav has been one of my favorite examples of a fiduciary executive. So, given Zaslav’s vision for DiscoMax, did I misread Zaslav as a fiduciary when he was actually a visionary?

Because DiscoMax is a visionary outcome both in value proposition - WarnerMedia’s and Discovery’s assets combined across linear and digital, globally - and the economics of its business model - it goes to market as a profitable business.

A fiduciary executive is strategically, operationally, and financially constrained within legacy business models. I think until this move for DiscoMax, Zaslav was constrained in his pursuit of a streaming model. Even in Q1 earnings, he was not forthcoming in how many of the DTC subscribers were discovery+ subscribers, and he was no longer selling the ongoing Amazon Food Network Kitchen as an example of Discovery’s success in innovating for streaming.

I think his vision for DiscoMax has compelling elements to it. But DiscoMax will not exist because Zaslav has been in pursuit of a broader vision for Discovery. Rather, Zaslav realized:

With Disney accelerating at that point because of COVID, I just looked at that and thought who could take that on? Who could be a global offering that formidable,” Zaslav said. “When you put us together — Batman, Superman, Wonder Woman, ‘Game of Thrones,’ ‘Sex and the City,’ HBO and Discovery being everywhere in the world with local content — we’re better together. I’ve been doing deals my whole life. The standard always is, are you better together? In this case were are not just better together. We are the best media company in the world, more global than anyone else with all the news, sports, entertainment and huge tentpoles that we bring together.”

In other words, Zaslav and Stankey were spooked by Disney+ growing by 21MM subscribers, and Hulu grew by 4MM between fiscal Q4 2020 and fiscal Q1 2021. HBO Max had gained 6.8MM new subs that quarter, and by February Discovery had gained 6MM. DiscoMax exists because Zaslav had a fiduciary duty to his shareholders for Discovery to find a way to survive and scale in a streaming marketplace where Disney and Netflix were dominating.

It is also worth asking whether Kilar’s rapid rise and fall reflect a failure of vision, or reflects negatively on visionary executives within legacy media organizations. I, for one, do not think Kilar’s departure reflects failure on his part. The optimal DiscoMax deal structure required a legacy media executive as CEO, and Discovery shareholder buy-in required that person to be Zaslav.

I think Kilar did an unusually good job under difficult circumstances. As Joe Flint wrote in his profile of Kilar for The Wall Street Journal last week, “Mr. Kilar inherited most of the hand he is playing from his predecessor, John Stankey”. He managed to grow both the subscriber base and revenues (up 30% on a stand-alone basis last quarter) for the HBO Max service during a once-in-a-hundred-year pandemic. Above all else, he navigated the ire of Hollywood to deliver a win-win outcome with producers and get movies released for theatrical distribution and day-and-date on the HBO Max service, too (and at the surprisingly low cost of $200MM, given the circumstances). That was his coup-de-grace move.

Maybe I am biased towards a positive outcome for #ReleaseTheSnyderCut campaign (and more sunlight into Ray Fisher’s dispute with Warner Bros), but there was something magical about Kilar’s run. HBO Max felt more accessible, vibrant, and consumer-savvy with Kilar as its consumer-facing corporate voice. AT&T was fortunate to have Kilar and his team at the helm. DiscoMax will feel his absence more than they have yet to realize or let on if they have realized it already.

Conclusion

I think as promising as the DiscoMax business model is for shareholders, I have difficulty envisioning it as a streaming powerhouse. I think that is the key takeaway from the Five Frameworks.

I think we have seen there are real limits in the assumption that B2B rebundling leads to scale. The largest SVOD services - Netflix and Disney+ - purposefully distribute outside of the B2B channels. Hulu, the largest AVOD service, does, too. Every other service that has reached a similar scale has leveraged B2B channels - IMDb TV, Pluto TV, The Roku Channel, Tubi TV- are all free services. But no service offering a low price point and ad-supported content has yet to scale.

Could that change? Sure. But I believe past is precedent: every legacy media offering that has opted for the B2B distribution partnership model has struggled to scale with those partners. That includes all offerings from ViacomCBS over the past five years (which have struggled to scale past 10MM subs until Paramount+’s relaunch), STARZ (14MM), and AMC Networks (6MM).

DiscoMax may offer shareholders a strong business model out of the gate. It certainly meets Barry Diller’s advice to “go big” and to “own nonfiction programming”. But, it risks not becoming “an essential streaming service” in the long run because it maximizes the decline of linear business over scaling streaming towards more consumers globally.

It would be a stretch to apply Co-opetition here. Bundling or rebundling is a form of co-opetition: nonfiction and fiction services believe they are better off together. But, DiscoMax is a merger: it creates an entirely new business for both WarnerMedia and Discovery, and an entirely new value proposition for both affiliate partners and advertisers, alike.

As for The Curse of the Mogul, DiscoMax can be evaluated by traditional strategic, financial or management appraisals. Zaslav may be overpromising with “[up to] 400 million homes over the long term”, but that is salesmanship. There is growing global demand for content across devices, and Discovery is better positioned than AT&T to meet that demand globally with WarnerMedia’s content library.

I think we will see the best reflection of Kilar’s understanding in October at DC Fandome, the event for which there were 22MM attendees worldwide in 2020. After Zack Snyder’s Justice League and the upcoming Suicide Squad movie, I imagine there may be as many as 40MM in October 2021.