Mic Drop #29: Jeff Bezos, Media Mogul and/or Media Visionary

Revisiting Amazon Prime's Fiduciary executives & Curse of the Mogul assessments

Brad Stone’s Amazon Unbound was released this week. Chapter 6, “Bombing Hollywood”, is all about Amazon’s efforts with Prime Video since 2013. It is an update The Everything Store, Stone’s first book on Jeff Bezos and Amazon.

It was this tweet from Recode’s Peter Kafka which convinced me to buy the book sooner than later:

Reading the chapter I was immediately struck by two things about Amazon Prime Video:

Bezos’ vision for Prime Video has been scientific in its approach (see above), and that has conflicted the more intuitive realities of the legacy Hollywood marketplace; and,

Prime Video has more Curse of the Mogul-type symptoms beyond a lack of disclosure of total subscribers and consumption metrics

Bezos as Flawed Visionary

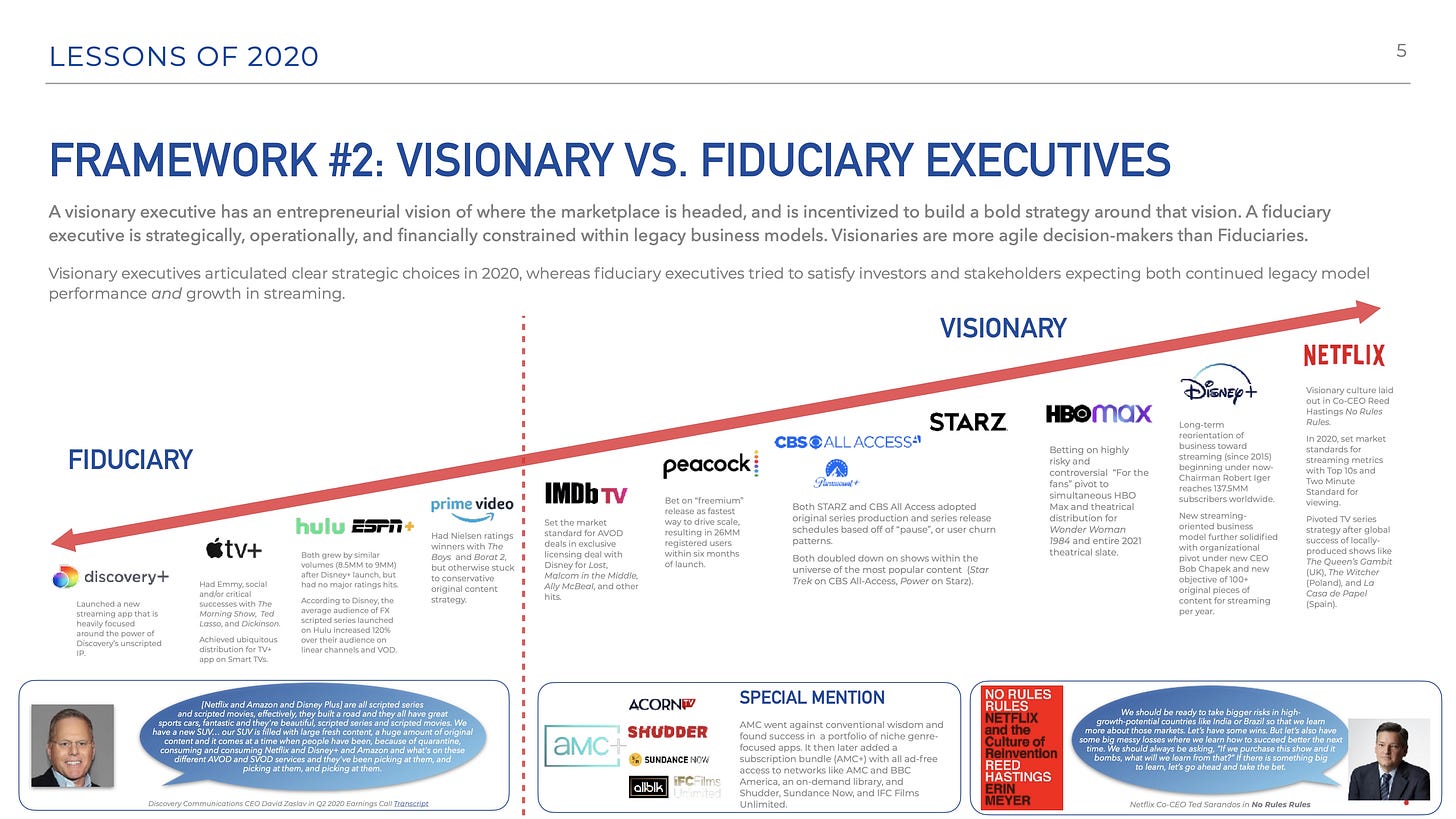

I’ve had a few debates with readers about why I put Amazon’s Prime Video more towards the Fiduciary end of the Visionary vs. Fiduciary spectrum in my Lessons of 2020 slides.1 Their counterpoint has been that Amazon Prime Video and its Amazon Studios content strategy are Bezos’s vision, Bezos is a proven visionary, so therefore Amazon Prime Video is a visionary business.

But, to date, Prime Video has had a conservative original content strategy relative to Netflix’s aggressive release strategy, despite operating at similar scale (200MM Prime subscribers worldwide). By offering limited content releases versus Netflix’s average of one show per day, Prime Video appears to be more conservative than Netflix.

In the “Bombing Hollywood” chapter, Stone mostly details the rise and fall of former Amazon Studios programming Chief Roy Price (precipitated by this Hollywood Reporter article), and how that shaped the programming strategy we are seeing today.

Bezos’s desire dates all the way back to 2004 to “rethink the entire Hollywood development process” and create “an entirely new approach, which he dubbed ‘the scientific studio’”. That created tension between Bezos’ more science-based approach (in the tweet above), and Price’s “unique sensibility for Amazon Studios” that took “high-quality indie films as their inspiration” to create “TV that was distinctive and sophisticated”.

This tension played out in 2016 and 2017 when Bezos wanted to find “a big show akin to HBO’s blockbuster Game of Thrones” to drive adoption of Prime Video when it was to be introduced into 242 countries. None of Price’s bets, like Transparent or Manchester by the Sea, met that criteria. By 2017 Bezos was growing impatient for more blockbuster content to help drive global adoption of Prime Video.

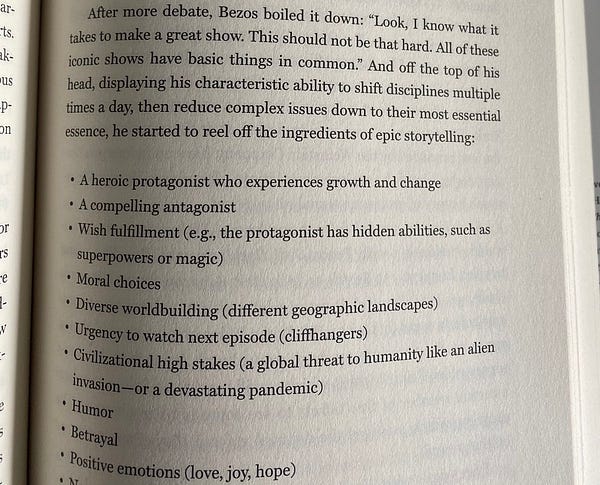

In a meeting in early 2017, Bezos introduced the “ingredients of epic storytelling” (in the tweet above) to push Price towards funding shows that met that these conditions, but:

Price told colleagues to keep the checklist from the outside world. Amazon shouldn’t dictate to accomplished auteurs the ingredients of a good story. Good shows should break such rules, not conform to them.

Price was fired in October 2017 because of a #MeToo scandal, and that changed the direction of Amazon Studios. But Stone notes:

Ironically, many of the shows that the scandal-plagued old guard put into production, like The Boys and Jack Ryan, would turn out to be global hits. Bezos continued to spend heavily on video. Prime Video consumed $5B in 2018 and $7B in 2019. There was continued debate on the actual return on this investment, though the objections from Amazon’s board and investors were not quite as loud.

Stone concludes that Prime Video was “yet another of Jeff Bezos’s big bets over a fruitful decade”:

By pointing the way for his employees over and over, closely monitoring their efforts, and using his own budding fame to magnify their visibility, Bezos had blazed a path into promising new technologies and industries.

So, it could be argued Bezos is a visionary, and Prime Video is his vision. The evidence is there from as good a source (Brad Stone) as any on the topic. Stone paints Bezos as being deeply involved as discussing which TV shows to greenlight with his team, and “fully attuned to the opportunities and challenges for building a successful film and TV business.”

But, Stone’s account reflects another dynamic: Bezos increasingly wanting “a scientific approach to creative decision-making” that was “not aligned” with Price’s belief that “sometimes [development executives] had to bypass the data and just go with their instincts”. This was especially true in competitive deals with in-demand TV producers and filmmakers.

So, even if “a scientific approach to creative decision-making” had worked for Bezos and Amazon more broadly, in Hollywood it faces the constraints resulting from both the creative process and the fast-pace of the marketplace for in-demand creative talent.

I think that tension has played out in Amazon’s original content efforts to date, and why we continue to see a fraction of original releases relative to Netflix’s efforts in the same space at 64% of Netflix’s spend ($17B). It is a tension between Bezos’s vision of more blockbusters and more data-driven decisions versus what Amazon Studios executives are reasonably able to accomplish against that vision in an increasingly competitive Hollywood marketplace.

So I think it’s reasonably accurate to put Prime Video at the line between Fiduciary and Visionary, tilted more towards Fiduciary.

Bezos & The Curse of the Media Mogul

The “objections from Amazon’s board and investors” on Bezos’s content spend have not been “not quite as loud”, even though it went up by 50% in 2020 to $11B from $7B. It includes $465B on an upcoming Lord of the Rings series. Content creators working with Amazon are capturing extraordinary value right now, and that value is growing. Stone writes about the justification for this content spend, above: there are objections from the board and investors but they are not loud.

The business rationale for the large and growing content spend was Bezos understanding the relationship between content and Prime before the Board of Directors did. The question is, what exactly is that relationship?

Bezos told a tech conference in 2016 “when we win a Golden Globe, it helps us sell more shoes”, but Stone writes that:

there was little evidence of a connection between viewing and purchasing behavior - especially one that justified the enormous outlay on video. Any correlation was also obfuscated by the fact that Prime was growing rapidly on its own.

This, and the “Bombing Hollywood” chapter more generally, are fodder for those who share the perception of this snarky quote from an anonymous Amazon engineer:

What’s an example of a division that AWS subsidizes particularly heavily?

Prime Video, for one. Jeff loves Prime Video because it gives him access to the social scene in LA and New York. He’s newly divorced and the richest man in the world. Prime Video is a loss leader for Jeff’s sex life

The Curse of the Mogul symptoms are evident at Amazon Prime - there is no direct or calculable ROI on billions in Prime Video spend, and a decision to charge separately for Prime Video globally was considered but passed over. Moreover, the board and investors are actively asking about and objecting to the content spend, even if they buy into Bezos’s vision for Prime Video.

But that said, Bezos’s approach is objectively scientific, trial-and-error, and data-driven. Curse of the Mogul-type symptoms can also be explained by the gap between his mindset, and Hollywood’s less rational, more intuitive mindset.

Maybe that’s why when Bezos told shareholders in his Q1 2021 earnings release last month:

“As Prime Video turns 10, over 175 million Prime members have streamed shows and movies in the past year, and streaming hours are up more than 70% year over year. Amazon Studios received a record 12 Academy Award nominations and two wins. Upcoming originals include Tom Clancy’s Without Remorse, The Tomorrow War, The Underground Railroad, and much more.”

175MM is a big number, especially given that there are now 200MM Prime members worldwide. But these two tweets summarize why it means little:

Even the biggest number Amazon has published for investors is an intangible in itself, and is not subject to traditional strategic, financial or management appraisals. It is anyone’s guess as to what it means.

Bezos may have a flawed, overly science-reliant vision for Amazon Prime Video. That said, because of his vision, 175MM Prime customers are getting better quality, more globalized content to consume as part of their Prime Membership, and Amazon is being nominated for Oscars, winning Golden Globes, and dominating third-party measurement charts. The vision has wins for customers and for Bezos in Hollywood, personally.

But, there are few, if any, traditional strategic, financial or management appraisals to tell us the value of Prime Video for Amazon shareholders. The Curse of the Mogul focuses on whether shareholders reap greater value from content investments like these, and it is not clear that they do other than as viewers.

The Return of Jeff Blackburn

Last, it is worth noting that with Bezos stepping down, and Andy Jassy taking over as new CEO, longtime Bezos S-Team deputy Jeff Blackburn is returning from a surprisingly short tenure at Bessemer Venture Partners (he joined in February) to become SVP of a new Global Media & Entertainment organization. He will oversee Prime Video and Amazon Studios, Amazon Music, Wondery and podcasts, Audible, games and Twitch.

Stone’s portrait of Blackburn in the “Bombing Hollywood” chapter is not entirely flattering: he was the company lead in dealing with the fallout of Roy Price’s #MeToo moment, and his explanations to employees of Amazon’s handling of the scandal are portrayed as having “rang hollow”,.

That said, Blackburn will report to Bezos until the CEO transition in Q3, and then he’ll report to Jassy.

Will Blackburn be a fiduciary constrained by Bezos’s vision?

Or a visionary who is more intimately familiar with the details of the streaming and media and entertainment businesses than Bezos?

I am in the process of rethinking these slides to simplify them for H1 2021. The deck may end up being longer but “less is more” as a guiding principle for each slide.