Monday AM Briefing #65

Need* to know stories and trends for this morning & the week ahead; A Short Essay on “Aggregator Bundling 2.0” & Convergence After Epic v. Apple

[Author’s Note: Thank you to those of you who voted. Right now, the top three, in order, are:

Revealing What's Hidden

Reframing Your Perspective.

[TIE] Reframing Thinking.

[TIE] Connecting the Dots Between Incentives & Execution.]

More to come on this soon. I’ll leave the link live for those who still may have an opinion.]

A Short Essay on “Aggregator Bundling 2.0” & Convergence After Epic v. Apple

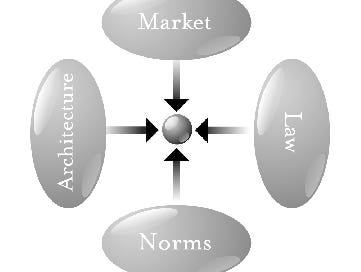

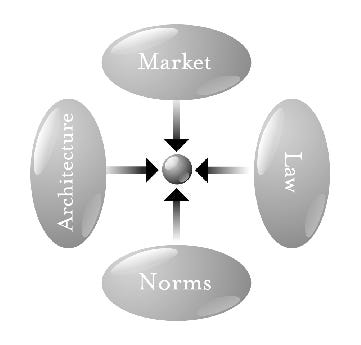

Below is a diagram of a “pathetic dot” from Larry Lessig’s book, Code 2.0 (PDF available here).

I like this drawing, and use it often.

Lessig writes:

In this drawing, each oval represents one kind of constraint operating on our pathetic dot in the center. Each constraint imposes a different kind of cost on the dot for engaging in the relevant behavior…

The easiest way to think about it as a checklist for understanding the constraints around a problem in any given scenario: the law, social norms (basically, ethics), marketplace dynamics, and/or technological infrastructure or “architecture”.

It’s particularly helpful when thinking about last Friday’s decision in the Epic v. Apple trial.

In “pathetic dot” terms, Epic’s antitrust complaint was that Apple was behaving as a monopolist in the broader mobile marketplace via its iOS software and App Store software (✅ Architecture Dot) and via its App Store (✅ Market Dot). Therefore a legal remedy (✅ Law Dot) was required.

I was a skeptic of Epic’s complaint last September (below). I’m not a practicing lawyer, but Epic’s original complaint defined Apple’s behavior in such a way that it read as a normative, moral plea for antitrust regulation than as a complaint based on existing antitrust law.

Epic founder and CEO Tim Sweeney frames the objectives of the legal case in broad, moralistic terms like “consumer freedom” and “fair competition” (✅Moral Dot). To use the “pathetic dot” framework, he seems to be caught up in a vision of antitrust as moral regulation than as legal regulation.

In fact, Lessig originally argued morality has a weak regulatory role in Internet businesses because cyberspace is amoral. I think that’s still true (so, ❌ Moral Dot).

Sweeney seems to ignore how the problems with the App Store seem more narrowly related to Apple’s regulation of the App Store Marketplace (✅ Market Dot), and Apple’s proprietary technological architecture for that Marketplace (✅ Architecture Dot).

I wrote my tweet, above, last year after reading a Bloomberg article about Japanese game developers experiencing similar issues to Epic. The article frames the problem less as one about antitrust law, and more about a disconnect between Apple’s management of the App Store and what its supply-side developer customers need (✅ Market Dot):

“Apple’s app review is often ambiguous, subjective and irrational,” said Makoto Shoji, founder of PrimeTheory Inc., which provides the rejection service. “Apple’s response to developers is often curt and boilerplate, but even with that, you must be polite on many occasions, like a servant asking the master what he wants next.”

It also may reflect a cultural disconnect between how developers expect to be treated in exchange for 30% of their revenues. But, it is not a legal problem (❌ Law Dot).

The ruling from Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers seems to see a similar problem in Epic’s complaint:

As a major player in the wider video gaming industry, Epic Games brought this lawsuit to challenge Apple’s control over access to a considerable portion of this submarket for mobile gaming transactions. Ultimately, Epic Games overreached. As a consequence, the trial record was not as fulsome with respect to antitrust conduct in the relevant market as it could have been.

That said, Judge Gonzalez Rogers found evidence of anti-competitive behavior in the App Store’s anti-steering provisions, which forces consumers to makes purchases within the App Store, only:

Because Apple has created an ecosystem with interlocking rules and regulations, it is difficult to evaluate any specific restriction in isolation or in a vacuum. Thus, looking at the combination of the challenged restrictions and Apple’s justifications, and lack thereof, the Court finds that common threads run through Apple’s practices which unreasonably restrains competition and harm consumers, namely the lack of information and transparency about policies which effect consumers’ ability to find cheaper prices, increased customer service, and options regarding their purchases.

Meaning, these problems may not reflect monopolistic control over the broader mobile marketplace or narrower mobile gaming marketplace (❌ Law Dot). Rather, it may reflect anti-competitive behavior emerging as a result of the software of that marketplace (✅ Architecture Dot, ✅Marketplace Dot).

In other words, Apple’s “interlocking rules and regulations” and the supply and demand of its installed iOS user base are what constrain a developer’s behavior within Apple. But those do not make a monopoly in the legal sense.

How feasible are “Aggregator Bundling 2.0” & “metaverse”-type Convergence After Epic v. Apple?

Because Epic CEO Tim Sweeney’s objective with the lawsuit is to build a “metaverse” without sacrificing 30% of his revenues to Apple, the Epic v. Apple has major implications for the marketplace feasibility of “aggregator 2.0” bundles and “metaverse”-type convergence.1

The logic of the “pathetic dot” diagram teases out two points about digital convergence:

the obstacle to “metaverse”-type convergence won’t be Apple or Google’s monopolies in mobile (❌ Law Dot)

the obstacle to “metaverse”-type convergence will be “the interlocking rules and regulations” of iOS and Android ecosystems and App Store marketplaces (✅ Architecture Dot, ✅ Market Dot).

This was all but confirmed in a CNBC piece last week:

But looking at App Store history, it’s likely that Apple will continue to push in private negotiations and public lobbying for smaller, non-structural changes to the App Store that address some complaints but does not change its control over iPhone software.

Effectively the choice for media companies seeking “metaverse”-type convergence is to innovate a new suite of services and apps based on “metaverse”-type convergence, and spend on additional marketing within the App Store to scale.

Or, they could simply to opt for the more conservative bet of third-party “aggregator 2.0” bundles, relying on third-parties to bundle their apps to drive growth and churn more predictably.

The choice seems obvious. I think this is why it is no accident that we are seeing the growth of “aggregator 2.0” bundles, where subscriptions across different services live outside the App Store and are centralized in user accounts at Verizon, T-Mobile, and AT&T.

Meaning, Verizon, T-Mobile, and AT&T may have more bargaining power to negotiate with Apple and Google to secure deals which circumvent the App Stores than media companies at a smaller scale (except, Disney, Netflix). And, “aggregator 2.0” bundles offer better business models than “metaverse”-type convergence,

I also think this is why it is no accident that, for all the chatter about the emergence of “metaverse”-type convergence, we are not seeing it yet in media. I wrote last month:

There is now more of an overarching business logic to [the “metaverse”] in 2021 than in 1992 with both cloud computing and DTC business models driving the gaming industry towards “Metaverse”-type models (e.g., Epic Games). But, beyond gaming there is still not much business substance to it, especially in legacy media.

After Epic v. Apple, one has to wonder whether the requirements for deeper software integration into Apple and Google’s App Stores (✅ Architecture Dot), sacrificing 30% of all in-app revenue ( ✅ Market Dot), and with little legal recourse (❌ Law Dot) are constraints too great for “metaverse”-type models.

Must-Read Monday AM Articles

Emerging "Metaverse"-type convergence strategies

The Verge offered a comprehensive breakdown of the Epic v. Apple decision. Also, Sean Hollister argues in The Verge that both Apple and Epic lost.

Apple settled the Japan Fair Trade Commission suit (above) by announcing will let developers of “reader” apps (think Netflix, Spotify, and Amazon’s Kindle app) directly link their customers to their own sign-up website.

Eric Seufert of Mobile Dev Memo unpacked Apple’s App Store policy changes

Metaverse companies are debating how they code user consent into their platforms.

Ben Munson of FierceVideo asks, “If AR [Augmented Reality] breaks through, could it spell doom for TVs?“

Aggregator 2.0

Hulu is increasing the price of its streaming plans from $11.99 to $12.99.

After Marvel’s ‘Shang-Chi’ smashed pandemic box-office records, and Disney announced all remaining 2021 movies will be distributed exclusively in theaters, this Streamable piece asks “Is Premier Access Finished?”

Netflix has begun to shed light on decision making at Netflix in the first of a series of blog posts. It also revealed in a SEC filing it has a new severance structure to better compete in retaining talent.

Sports & Streaming

CNBC’s Alex Sherman reports Amazon is the likely front-runner for multiyear NFL Sunday Ticket deal after DirecTV’s deal expires.

Verizon and the NFL extended their longstanding relationship with a 10-year marketing and tech deal, but Verizon will no longer going to be livestreaming football games on mobile. The deal is firmly focused on 5G.

Users of Peacock TV, one of the only places in the US where fans can watch Premier League soccer matches, reported widespread disruptions trying to stream games live on the service on Saturday.

Bloomberg’s Lucas Shaw has a must-read interview with former DAZN Chief John Skipper.

Creative Talent & Transparency in Streaming

The livestreaming boom is driving a significant uptick in the creator economy, as a new forecast from App Annie estimates consumers will spend $6.78 billion in social apps in 2021, and will grow to $17.2 billion annually by 2025.

Of the 426 post-IPO SPACs which have not yet announced a deal, the average is trading 31 basis points below its IPO price. In other words, investors are assuming that target companies will be increasingly undesirable.

Lion Forge Animation is a mission-driven animation studio based in St. Louis that is dedicated to bringing diverse voices and stories to both small and large screens. Fast Company profiles how it is “changing Hollywood” after an Oscar win for Hair Love.

Original Content & “Genre Wars”

The New York Times’ Dave Itzkoff had a deep dive into TCM’s rebrand within WarnerMedia and HBO Max.

HBO Max is coming to Europe on Oct. 26, and the first launch markets will be Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Spain and Andorra.

Judge Judy Sheindlin’s new IMDb TV original series, officially called “Judy Justice,” is set to premiere Nov. 1 exclusively on the Amazon-owned free streaming service. The show sets up an interesting test for IMDb TV to see whether it can attract and retain a loyal daily audience.

I missed this summary from last month of FX Chief John Landgraf discussing his new, FX-centric role at Disney post reorg.

Hollywood scribe Paul Schrader tells GQ: “It’s not that the filmmakers have changed, it's that the audiences have changed. And when the audiences don't want serious movies, it's very, very hard to make one.”

Roku has confirmed that it has picked up a holiday-themed, feature-length film based on NBC’s canceled musical comedy “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist” to air exclusively on its ad-supported The Roku Channel in the U.S. later this year.

Comcast’s & ViacomCBS’s Struggles in Streaming

ViacomCBS pushed out Paramount chief Jim Gianopulos and replaced him with Nickelodeon Chief Brian Robbins because Robbins, the former head of youth-focused film and television entertainment company AwesomenessTV, is more attuned to demands of the streaming age.

“Halloween Kills,” the upcoming entry in Universal’s slasher franchise, will debut on Peacock on the same day as its theatrical release.

AVOD & Connected TV Marketplace

Insider’s Tanya Dua and Lauren Johnson revealed exactly how HBO Max, Hulu, and Roku are charging for streaming ads. ($ - paywalled)

Insider’s Elaine Low dove into Pluto TV’s programming strategy ($ -paywalled)

Nielsen CEO David Kenny predicts industry accreditation will be back sooner than many people think. Mike Shields asks and answers “Who replaces Nielsen? Maybe Nobody”.

A Next TV piece argues that Roku's message that TV stremaing has passed “a tipping point” however, seems to be in some conflict with recent revealing data published by Nielsen, which said that video streaming only account for 28% of overall U.S. TV consumption in July.

The FAST marketplace is evolving so rapidly it is becoming like a “gladiator pit’, argues Cinedigm’s Erick Opecka.

Epic v. Apple decision offers one definition for “metaverse” which has been elusive to date:

The Court understands that, based on the record, the concept of a metaverse is a digital virtual world where individuals can create character avatars and play them through interactive programed and created experiences. In Mr. Sweeney’s own words, a metaverse is “a realistic 3D world in which participants have both social experiences, like sitting in a bar and talking, and also game experiences....” In short, a metaverse both mimics the real world by providing virtual social possibilities, while simultaneously incorporating some gaming or simulation type of experiences for players to enjoy.