Member Mailing #257: The PARQOR Hypothesis Predicts Streaming in 2025

We learn that in 2025 the best strategies will be to aim to be Disney, or aim to own a genre

A Quick Note

I had a variety of feedback on last week’s post, all of which came from good conversations with readers fascinated by the market dynamics around an ad buyer’s potential choice of buying from Amazon or NBCU.

I believe the piece did a good job capturing those market dynamics. I am less convinced the piece needed to be as technical as it was: the market dynamics are so much more interesting than their technicalities. If I were to re-write it, I would structure it around the four most obvious outcomes for ad buyers:

Buy from both Amazon and NBCU (Thursday Night and Sunday Night)

Buy from Amazon but not NBCU (Thursday Night only)

Buy from NBCU but not Amazon (Sunday Night only)

Buy from neither NBCU nor Amazon, and instead buy from third-party programmatic (e.g., Trade Desk) (Programmatic only)

Permutations emerge within each outcome (e.g., buying direct and/or programmatic), but my takeaway from conversations with readers is that these four are the fundamental dynamics at play.

I highlight them because I plan on returning to this market dynamic, and this will be a helpful outline for doing so.1

Key Takeaways:

The value of the PARQOR Hypothesis framework is that it frames the streaming marketplace into two groups:

Companies that meet all five BEADS attributes, and

Companies that do not (yet) meet all five BEADS attributes

If there are two key variables in the marketplace worth keeping an eye on for these companies, it is the dynamics around Aspirational Brand and Offline Sales Channels.

In 2025 the best strategies will aim to be like Disney and meet all five BEADS attributes, or aim to own a genre.

AVOD, in one form or another, seems to be a common solution for expanding the Total Addressable Market (TAM) for all of these services beyond SVOD. But, launching an AVOD tier comes with complicated questions about branding.

I spoke with an executive at one of the major streaming services last week, and I asked him what pain points they were evaluating or trying to think through.

One question he had was forward-looking: what is the future of streaming in the media marketplace? Or, to simplify the question: where is this all headed in 2025?

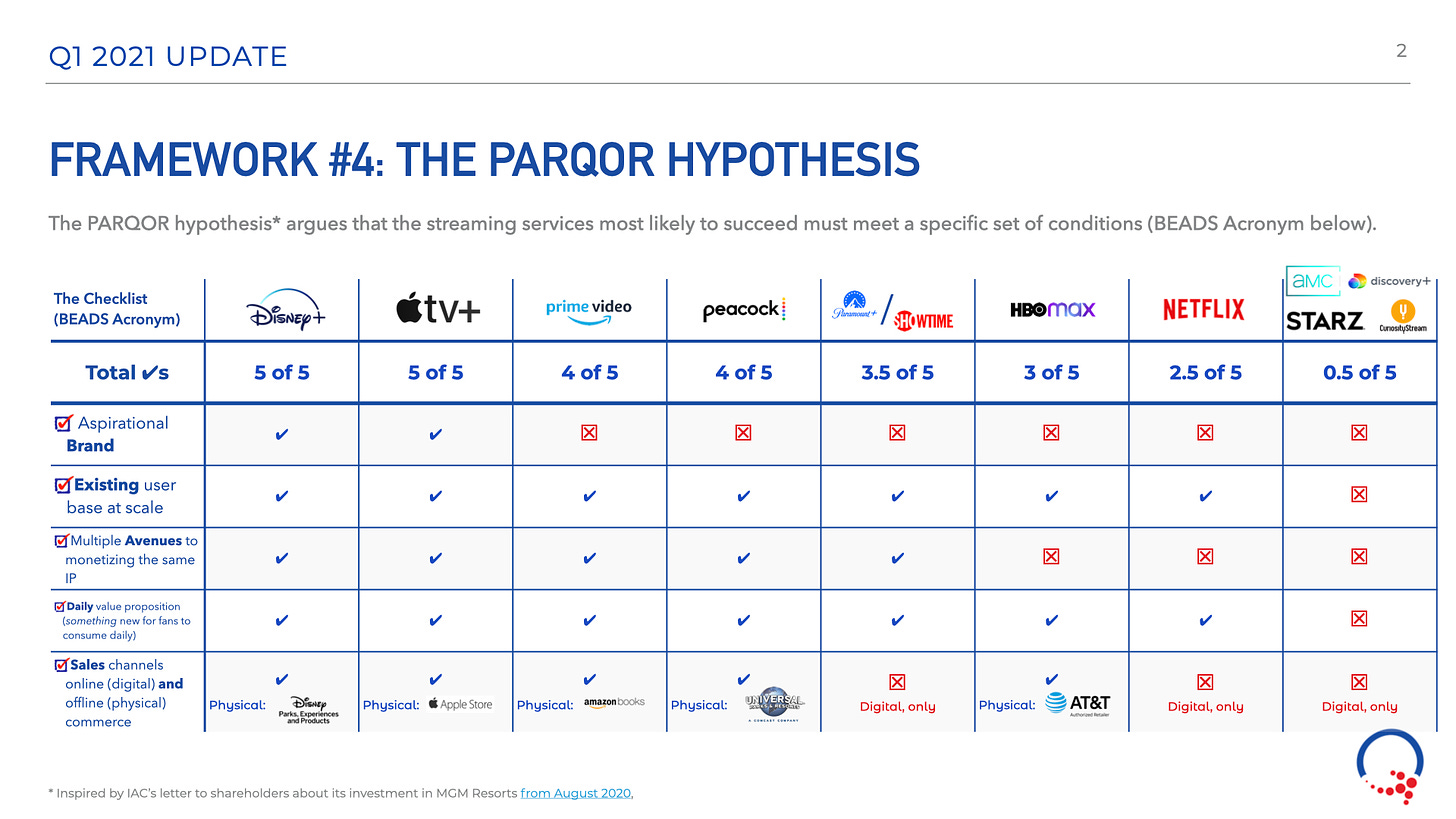

I think the PARQOR Hypothesis is a valuable framework for answering that question (below is the updated chart for the Q1 update to my PARQOR Learnings and Predictions Deck).

If we take the PARQOR Hypothesis at its most basic, it frames the streaming marketplace into two groups:

Companies that meet all five BEADS attributes, and

Companies that do not (yet) meet all five BEADS attributes

I think those are two reasonable outcomes for the streaming marketplace in 2025 because they each succinctly summarize the difference in long-term strategies between a Disney and a STARZ. The former sees upside in centralized, data-driven consumer ecosystems, and the latter sees upside in serving “underserved” audiences globally.

Will companies that meet all five BEADS attributes still be ahead of the competition in 2025? The PARQOR Hypothesis tells us that those companies, and also those companies furthest from meeting all five attributes, seem to have the most certain futures for 2025. Everyone else is a question mark, including (surprisingly) Netflix.

In short, in 2025 the best strategies will aim to be like Disney and meet all five BEADS attributes, or aim to own a genre.

Companies that meet all five BEADS attributes

There are only two companies that meet all five BEADS attributes in 2021: Disney and Apple. It is likely this will still be true in 2025.

An IAC investor memorandum, and a fun, snarky analogy to golf from IAC Chairman Barry Diller to The New York Times’ Ben Smith, both made the compelling case as to why the BEADs acronym has set Disney apart from the rest of the competition.2

The question is how will their respective streaming strategies will have evolved by 2025? Because their respective strategies in streaming have evolved exponentially over the past year:

Disney launched with four streaming services (Disney+, ESPN+, Hulu, Hotstar) and now has six with Star and Star+

Apple TV+ launched with a handful of big Hollywood shows, but now is gaining momentum with the surprise success of awards darling Ted Lasso, more positive critical reception to For All Mankind, and its upcoming lineup of 31 series, 7 features and 9 documentaries (and growing).

Disney has projected its portfolio of apps will have 300-350MM subscribers by FY 2024 (~30% or ~100MM will be Hotstar), the streaming business will be profitable, and content spend will be $14 to $16B. By then it will also have released “‘roughly’ 10 Marvel series, 10 Star Wars series, 15 Disney live-action, Disney Animation, and Pixar series, and 15 all-new Disney live-action, Disney Animation and Pixar features directly to Disney Plus.”.

Apple has been more opaque with its projections for Apple TV+: it is a key element of the Services business, which is growing steadily at 16% Year-over-Year to $54B annually, and has grown by $14B since 2018. But Apple TV+ is not key to that growth: Apple reports higher net sales from the App Store, advertising and cloud services than from Apple TV.

Apple is investing up to $6B in original content, so the onus for where Apple TV+ ends up in 2025 is on whether its bets on 31 series, 7 features and 9 documentaries will succeed (and growing).

Both companies are in the early stages of their longer-term game plans for streaming. By 2025, we will be measuring their efforts against the success of their content slate, and how their BEADS models have evolved since.

Companies that do not (yet) meet all five BEADS attributes

It is more difficult to imagine how 2025 will play out for companies that do not (yet) meet all five BEADS attributes. Because there are a variety of objectives driving each of these companies:

BEADS is the objective

BEADS is not the objective, but is within reach, and

BEADS is not the objective, ever (Genre Wars).

There is a longer essay (more likely a series of essays) to be written on each of these three sets of objectives. For the purposes of this essay, I am going to focus on what distinguishes each of these three objectives.

BEADS is the objective

When BEADS is the objective, the Disney model is the objective, according to IAC.

Netflix is the only business that has explicitly stated that Disney’s BEADS model is an objective. Surprisingly, according to the PARQOR Hypothesis, it is also one of the furthest away from it with 2.5 attributes checked off (above).

The question for 2025 is what Netflix needs to solve within the BEADS framework. There are three attributes it lacks:

an Aspirational Brand

Multiple Avenues to monetizing the same IP, and

offline Sales Channels

It is not clear how Netflix solves for being an “aspirational” Brand: if anything, within the past 12 months Netflix’s brand has evolved from Hollywood-centric content to more animation and foreign-language content. It is much more a democratized brand.

We do know Netflix has been experimenting with Multiple Avenues to monetizing the same IP and offline Sales Channels with a Stranger Things drive-thru experience in Los Angeles, CA.

But its biggest focus has been building out a library of original IP, with an increasing focus on animation. Better IP, or “the titles you can’t live without”, solves for multiple revenue sources (theme parks, merchandise) and Brand.

Netflix management speaks in terms of thinking in terms of “decades to come”, as COO Greg Peters told investors in Q3 earnings. So by 2025, the question will be whether its ~$20B in annual spend on original content will have resulted in long-term IP its Existing user base at scale “can’t live without”.3

BEADS is not the objective, but is within reach

When BEADS is not the objective, but is within reach, companies are a move or two away from a Disney-like media business model.

Four companies fall into this group:

Amazon Prime Video,

NBCU’s Peacock,

ViacomCBS (Paramount+, Showtime), and

WarnerMedia’s HBO Max.

All have one thing in common: none are Aspirational Brands.

HBO Max could be argued to be an Aspirational Brand because HBO has historically been an aspirational brand. However, it is important to remember AT&T created the Max brand with the intent of reaching a larger audience than HBO’s linear brand. Its upcoming, lower-priced HBO Max AVOD tier (June 2021) suggests WarnerMedia is trying to create expand that audience for the HBO brand, or a broader Total Addressable Market (TAM), even further with a lower price point.

Recent branding decisions at ViacomCBS’s Paramount+ and NBCU’s Peacock raise a different question: what does it mean when a service opts for a brand that both limits the TAM in certain markets, and expands it in others?

Paramount as a brand is more recognizable outside the U.S. because the Paramount Network is ViacomCBS’s international cable network. It distributes the Paramount Pictures film catalogue and selected TV series from ViacomCBS's television productions across Europe, Latin America and Asia. But, in the U.S. it is less recognized than CBS, the previous brand for Paramount+. Notably, neither Paramount nor CBS is an aspirational brand.

As for NBCU’s Peacock, its brand is limited to the U.S. and is a new brand related to NBC’s historical logo. For international audiences, Comcast and NBCU are now considering the Universal brand (as I wrote about yesterday).

An interesting question raised by this news is whether, by “aspirational”, IAC’s assumption is that audiences “aspire” to Disney’s brand in part because it offers theme parks. If this is true (I think it is reasonable to believe this is IAC’s assumption), “Universal” may be closer to an aspirational brand than Peacock because Universal Parks & Resorts is a theme parks business. With a rebrand of Peacock, or even by offering a new, more premium Universal service, NBCU could meet all BEADS conditions.4

The challenge with the theme parks business is that, if pre-COVID NBCU, ViacomCBS, and WarnerMedia were risk-averse to own a theme parks business, it is hard to imagine they are more open to the possibility during an ongoing pandemic which has been brutal to Disney’s and Universal’s theme parks businesses: in 2020, Disney reported as much as $2.4B in losses in operating income, and Universal Theme Parks swung from nearly $3 billion in profit to $500 million in losses in 2020. Six Flags, now with a market cap of $4B (up 2x since I wrote about them last month) lost $1.13B in 2020, and $758MM in EBITDA.

Post-COVID, neither ViacomCBS nor WarnerMedia seems to be operationally or financially prepared to shift focus away from their existing streaming strategies - which are capital intensive on their own - to take on more operational risk in a new vertical that is also capital intensive. So it is unlikely they will be in the theme parks business, too, by 2025.

Last, Amazon Prime Video is an interesting business because it is now aggressively building out a premium library, restructuring its Studios team, and expanding its sports offerings (the NFL deal, Yankees baseball) for Prime Video subscribers. It is also simultaneously building out a free tier with its new free AVOD, IMDb TV. This move could be interpreted as Amazon seeking to make Prime Video a more aspirational brand, and IMDb TV a more accessible brand.

If this is indeed its strategy, by 2025 Amazon may redefine Prime Video to become a BEADS service, too, similar to Apple TV+.

BEADS is not the objective, ever (Genre Wars)

When I coined the term “the genre wars”, I defined it as:

…one way to think about product channel fit in streaming is to think of the “streaming wars” more as ‘the genre wars”, which are more like focused, zero-sum conflicts around specific content genres than broader head-to-head, zero-sum conflicts between platforms for the same audience.

Two weeks ago, in “AMC Networks, Starz & "Genre Wars" Strategies”, I dove into the distribution strategy, economics and churn of these services. The common theme to all of them is: BEADS is not the business objective, ever. They are each and all happy focusing on both content verticals and/or specific demographics.

The interesting question is, can that strategy continue through 2025? For both Starz and AMC’s suite of apps, I concluded in that essay:

..although only one app, Starz may have long-term advantages over AMC because of its narrow focus on converting particular demographics. AMC seems less focused by comparison, and “volatile” churn may betray the weaknesses of a lack of focus in a “genre wars” model.

For AMC in particular, I wondered whether it had spread its bets too thin across five different apps:

Meaning, there may be a compelling business rationale to pursue five different apps across five different genres. However, because this model implicitly has more volatile churn than the Starz app alone, there is also very good evidence that the “genre wars” strategy requires going deeper with specific audiences with fewer apps.

I also asked about AMC operating both linear and streaming businesses:

“what is operationally required of AMC to scale five apps alongside running linear channels facing declining linear audiences?”

There is a risk that approach leaves both streaming and linear businesses sub-optimally monetized between today and 2025.

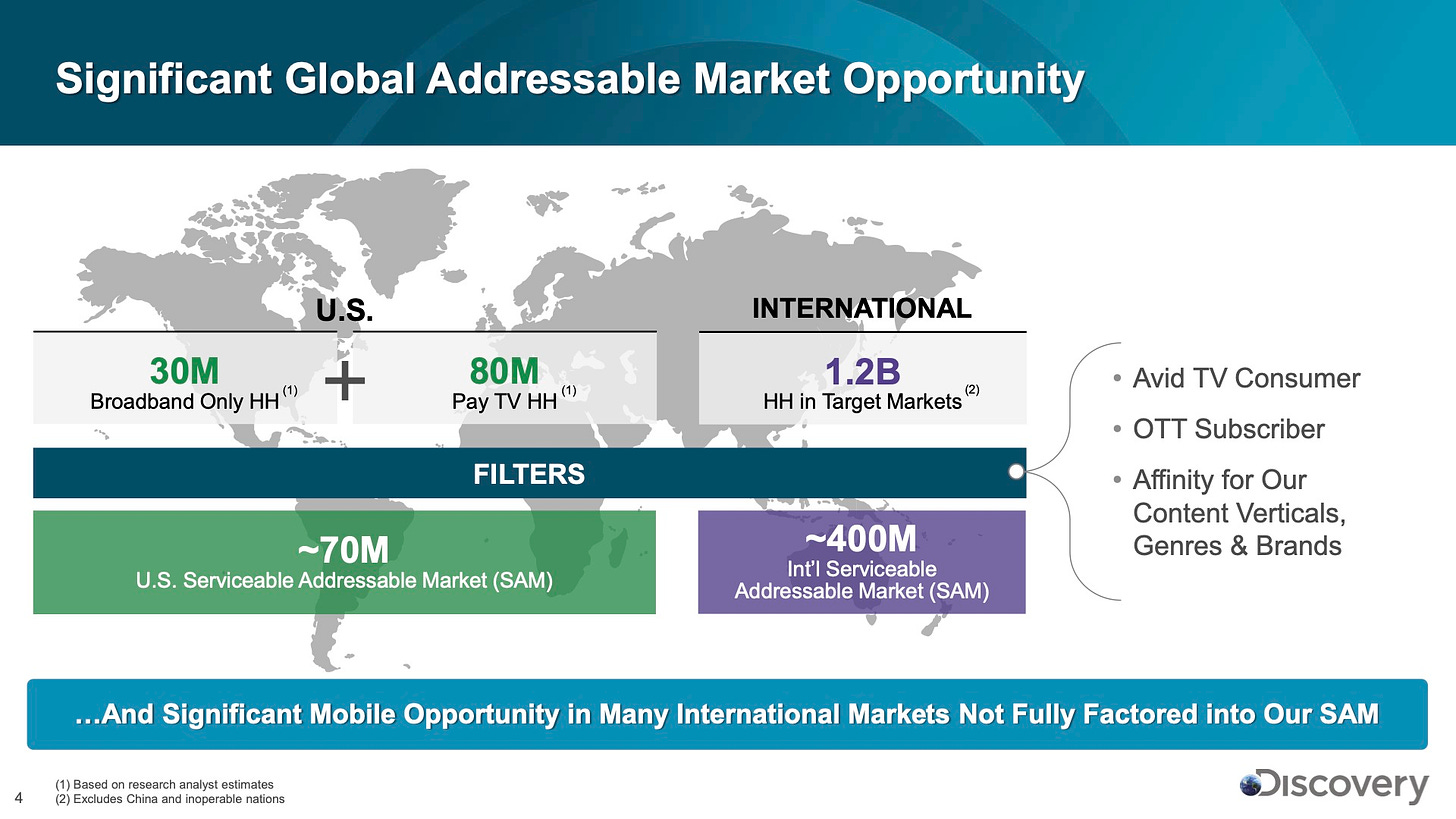

I think Discovery faces this risk, too, though I increasingly buy into the argument that discovery+ will be a niche service that makes passionate fans of Discovery talent and shows happy. So, for now, it appears there seems to be a low risk of streaming cannibalizing ~$11B of domestic and international networks revenues, or of Discovery sub-optimally monetizing both streaming and linear businesses. There seems to be healthy market demand for both (below).

Last, it is worth highlighting how CuriosityStream’s revenue model is not betting on direct-to-consumer revenues, only. Rather, it is betting on five different revenue streams, as I wrote about in CuriosityStream ($CURI) and the Launch of discovery+ ($DISCA):

Direct and partner Direct: consumer devices, MVPDs and vMVPDs

Bundled MVPD: affiliate relationships with MVPDs, broadband and wireless companies in the US and international territories offered a broad scope of rights, including 24/7 “linear” channels, an on-demand content library, mobile rights and pricing and packaging flexibility, in exchange for an annual fixed fee or fee per subscriber as part of a multi-year agreement

Corporate and Education: selling subscriptions in bulk to companies, organizations, schools, universities and libraries

Sponsorship & Advertising: Spot advertising on linear networks

Program Sales: providing factual content for the launch of a major SVOD program service in the US, and selling selected rights to content we create in advance of production, thus reducing risk in our content development decisions while delivering revenue

There is little, if any, need for CuriosityStream to pursue a BEADS-like model.

AVOD

It is worth briefly revisiting a point about Amazon and IMDb TV: AVOD services allow for a media company or a platform to create a more accessible, free tier for broader audiences while reinforcing the “premium” value proposition of the subscription service.

ViacomCBS has the most similar brand strategy to Amazon’s strategy with Prime Video and IMDb TV, leveraging the success of its PlutoTV brand to reinforce the premium value proposition of its Paramount+ and Showtime SVODs.

NBCU launched Peacock as a three-tiered brand, but is now weighing a choice between the Peacock and Universal brands in ad-free subscription tier, both internationally and possibly domestically (see above, and as I wrote yesterday). This outcome may result in Peacock downgraded into a two-tier AVOD service, and Universal Stream its streaming service.

WarnerMedia has opted for a similar decision to Peacock’s original strategy, making the HBO Max brand accessible for AVOD.

Last, Disney opted to keep Hulu and ESPN+ as AVOD brands in the U.S. (and recently launched ESPN+ within Hulu) and is now rolling out Star+ in Latin America (which will serve ads against sports content, but it is still unclear whether it will also serve ads against original content, too).

AVOD, in one form or another, seems to be a common solution for expanding the TAM of all of these services. But, launching an AVOD tier comes with complicated questions about branding.

Conclusion

After 2020, the exercise of predicting 2025 is effectively a fool’s errand: very little we believed to be true in 2019 is now true in March 2021. So there is little reason to believe that any predictions in 2021 will be true in 2025.

That said, the value of the PARQOR Hypothesis framework is not that it is prophetic. Rather, it provides an optimal outcome for 2025 which two market participants (and one non-participant, MGM Resorts) have already achieved, and against which we can assess each streaming service’s existing business models, objectives and strategies.

The framework sheds a particularly dynamic light on companies that fall under “BEADS is not the objective, but is within reach”. If there are two key variables in the marketplace worth keeping an eye on for these companies, it is the dynamics around Aspirational Brand and Offline Sales Channels. For the majority of those services, they all seem to be facing the same pain point for 2025: if the TAM for their subscription-only services is limited by price or by brand, how will they solve for either (or both, in the case of Peacock)?

Notably, they are each and all solving for that pain point in different ways. By 2025, we will know which companies had the smartest solutions. For now, it is too early to tell.

Last, it is also worth noting that Netflix remains the big question mark through the lens of the PARQOR Hypothesis. It is interesting to return to the observations of IAC Chairman Barry Diller, who thinks that “Netflix has won the game” in streaming, and who also thinks Disney is the only legacy media company that will “remain relevant into the future”.

The lens of the PARQOR Hypothesis implies there is a disconnect between both observations: the best business model for streaming in 2025 will be Netflix’s, but the business model for media businesses with streaming models in 2025 will be Disney’s and Apple’s.

What makes the disconnect particularly notable is that Netflix openly discusses how Disney’s model is its long-term objective, as I wrote in “AMC+(AMCX) & Shudder, Netflix ($NFLX) & Animation, and Product Channel Fit”:

I had not thought of Netflix engaging in “genre wars” until I read this eyebrow-raiser of a quote from Netflix co-CEO Reed Hastings:

“We want to beat Disney in family animation,” says Hastings when asked what area of programming he felt that the streaming giant, which releases hundreds of titles around the world each year, has yet to master. “That’s going to take a while. I mean, they are really good at it.”

Add to that Hastings told The New York Times when asked which writers are “especially good on the workings of the entertainment industry”, he answered Neal Gabler (biographer of Walt Disney) “for historical perspective”, and Disney Chairman Bob Iger “for the inside view”. Hastings very much has his eyes on the animation prize.

What will this mean in 2025? Of bets on original IP, it is making today, Netflix will likely have more wins in animation and kids content.5 In fact, most of Disney’s competition is shaping up to have more wins. But it remains less clear how Netflix is going to solve for both an Aspirational Brand and offline Sales Channels by 2025.

Netflix’s extraordinary strengths lie in its software and “ubiquitous access” (on-platform and off-platform marketing). Its extraordinary weaknesses lie in Aspirational Brand and offline Sales Channels, which are its stated objectives. How, or whether if, Netflix solves for those objectives will significantly shape how the streaming marketplace in 2025 will look like.

It also invites a 2x2 matrix image, which I will get to after I finish my Q1 update to my PARQOR Learnings and Predictions Deck

“Disney will remain relevant into the future,” said Barry Diller, who once headed Paramount and Fox and is now chief executive of the digital media company IAC. “All of the rest of them are caddies on a golf course they’ll never play.”

I dove deep into this question last September in “Netflix ($NFLX) Needs International Growth Now, When Will It *Need* Franchise IP?”

I missed this implication in yesterday’s piece.

Universal Theme Parks also sets up NBCU to be a crucial partner or merger candidate for any service which wants to solve for Multiple Avenues for monetizing the same IP and offline Sales channels. Six Flags, at its current $4B market cap, seems to be an obvious acquisition candidate for WarnerMedia given its licensing deals for DC and Looney Tunes IP, and ~33MM annual visitors in 2019. But, we have not been hearing those rumors (yet), as logical as they may seem through the lens of the BEADS framework.

What’s On Netflix has a good ongoing series on kids content on Netflix from ex-Disney executive Emily Horgan